Sahan Journal’s climate coverage is supported by a generous gift from Morgan Family Foundation. You can become a sponsor, too.

Molecular biologist Raven Baxter noticed a bug bite on her dark brown skin during the pandemic, so she did what most people do: looked up images of tick bites online to decide how to treat it.

The only problem: She found just one picture of Black skin featuring the bull’s-eye rash that can signal tick-borne Lyme disease. If you search Google images of “Lyme disease rash,” hundreds of images of the rash on white skin pop up.

“What does a tick bite look like on someone like me or with super rich skin from Sudan???? We get bitten too and need to know what that would look like!” tweeted Baxter, who works at the University of California, Irvine.

Baxter’s post clicked with Dr. Dan Ly, a physician and an assistant professor at the University of California, Los Angeles. When he also came across a New England Journal of Medicine piece on the lack of images of Black skin in medical education, Ly decided to look into the consequences of textbooks featuring only white skin. And in the case of tick bites and Lyme disease, Ly found a major problem.

He discovered that Black patients were diagnosed with Lyme disease–an inflammatory disease caused by a bacteria carried by blacklegged ticks–at a much later stage of the illness than white patients. His study indicates that people of color need to be vigilant about preventing Lyme disease.

Lyme disease is the most common vector-borne illness in the U.S. The infection initially causes symptoms such as fever, headache, fatigue, and often the bulls-eye rash called erythema migrans. When not treated, infection can affect the joints, heart, and nervous system. Minnesota has averaged about 1,000 reported cases of Lyme disease every year, up sharply from about 200 a year in the 1990s.

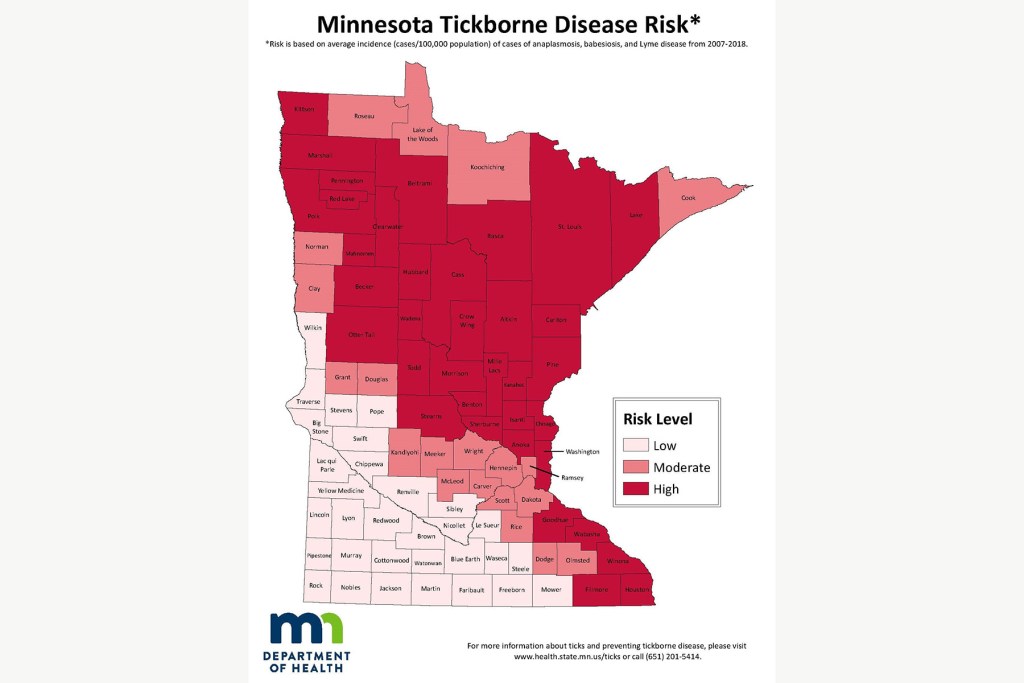

For Minnesotans of color, the risks are multiplied both by skin color and location: Minnesota has long been a hotbed for ticks, and climate change is encouraging blacklegged ticks to extend their season and non-native ticks, that carry other diseases, to expand their range north.

“Tick season starts as soon as the snow melts and people head outside,” said Mayo Clinic parasitologist Bobbi Pritt, whose work includes developing better tests to diagnose tick-borne diseases.

Blacklegged ticks are most active throughout the spring, when they’re smallest and hardest to spot (not much bigger than the period at the end of this sentence.) Activity dies down a bit in the late summer, but can ramp up again in the fall — just in time for hunting season, said Elizabeth Schiffman, supervisor of the vector-borne disease unit at the Minnesota Department of Health.

Delayed diagnosis means less effective treatment

Ly analyzed Medicare data from 2015 and 2016 that indicated how the disease was diagnosed. A rash is an early sign of Lyme disease, whereas symptoms such as arthritis and neurological symptoms show up later. Ly found that 34 percent of Black patients were diagnosed with neurologic symptoms compared to 9 percent of white patients. In other words, the illness was typically diagnosed earlier in white patients. Ly’s study appeared last fall in the Journal of General Internal Medicine.

“I wasn’t surprised that I found a difference, but I was surprised by how large that difference was,” he said in an email to Sahan Journal.

That’s significant because a delay in diagnosis can mean the difference between receiving effective treatment or not. Doctors commonly prescribe oral antibiotics to treat the disease, and that is most effective when started as soon as possible after infection. There’s currently no approved vaccine for Lyme disease.

Late-stage Lyme disease can be treated intravenously with antibiotics, which have more side effects than oral antibiotics. The disease can also have long-term consequences, such as extreme fatigue, when not treated early.

A study from 2000 published in the American Journal of Epidemiology warned: “Geographic spread of the disease warrants efforts to increase awareness of Lyme disease and its manifestations among people of color and the health care providers who serve them.” But there has been scant research on diagnosing Lyme disease in people of color.

Ly found just one case study since the 2000 report, which also reached the conclusion that people of color could be diagnosed later than white patients.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimates that about 476,000 Americans get treated for Lyme disease every year, even though states report only about 30,000 cases.

Not every state reports the race of patients with Lyme disease, but those that do show the vast majority of patients are white. Minnesota doesn’t break down its data by race; numbers for people of color have been so low that the data hasn’t been helpful, said Schiffman. The department of health hopes to add race to its Lyme disease data in the future, she said.

That significant difference in diagnosis rates has often been chalked up to where people live. But Ly’s study suggests that since doctors usually rely on symptoms to diagnose the disease, people of color with Lyme disease may be less likely to show up in official statistics.

This system needs to do a better job of representing racial and ethnic minority patients so that physicians can deliver better care to these patients, and it needs to do a better job of helping such patients become more aware of the signs and symptoms of Lyme disease and of other diseases so they know when to go to the doctor.

DAN LY, ASSISTANT PROFESSOR AT THE UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, LOS ANGELES

“My results suggest that, regardless of whether there’s general underdiagnosis, there is likely more underdiagnosis of Lyme disease in Black patients relative to White patients,” he wrote in an email to Sahan Journal.

The health-care system has effectively taught physicians and white patients to recognize the signs and symptoms of the disease in white patients, he said.

“But that same system has done a poorer job in helping physicians and Black patients recognize those signs and symptoms in Black patients,” he said. “This system needs to do a better job of representing racial and ethnic minority patients so that physicians can deliver better care to these patients, and it needs to do a better job of helping such patients become more aware of the signs and symptoms of Lyme disease and of other diseases so they know when to go to the doctor.”

Climate change multiples risk

The blacklegged tick (also known as a deer tick) and the American dog tick (also known as a wood tick) thrive in Minnesota. Lone star ticks, previously found in Southern states, have been moving further north in recent years. Although they do not appear to be established in Minnesota yet, researchers think the ticks will eventually make Minnesota home as winters warm. Lone star ticks carry different diseases than blacklegged ticks.

Climate change can help blacklegged ticks, which spread Lyme disease, thrive as well, said Jean Tsao, an associate professor at Michigan State University who studies ticks. (The bigger, American dog ticks can be a nuisance but rarely carry diseases that affect humans in northern climates.) Blacklegged ticks need to feed once at each of their three life stages.

“If winter is shorter with spring starting earlier and fall going longer, that gives ticks a lot more time for the different life stages to find a host,” she said.

In other words, climate change can make tick season longer–almost year-round, she said.

Without a vaccine or widespread methods of controlling ticks in the field*, prevention of tick bites is key to curtailing tick-borne diseases, she said.

related stories

Tips for tick prevention and treatment

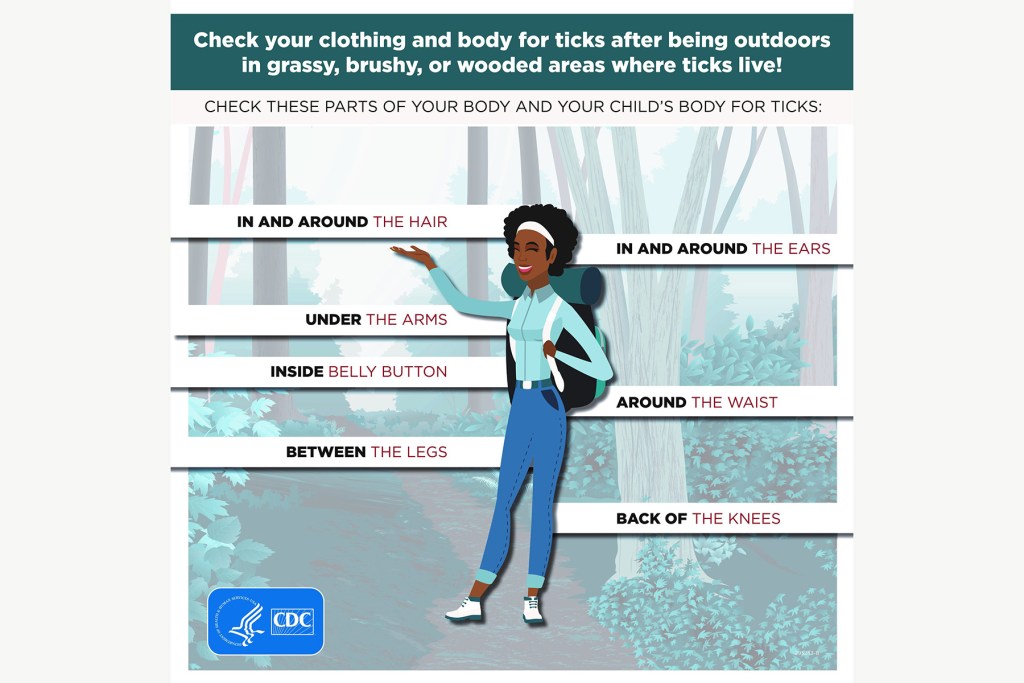

If you imagine a classic scene of the Minnesota outdoors–leafy trees and brushy areas–that’s the habitat ticks like, Schiffman said.

“Ticks like to be out in the same kind of weather that humans enjoy,” she said.

If you’re planning on spending time in an area that could be tick habitat (any area where you may see deer), Pritt recommends using the ABCs of tick prevention:

- A: Avoid areas ticks enjoy, such as wooded areas with leaf litter or tall grasses.

- B: Use bug spray if going outdoors.

- C: Cover up skin when heading into tick habitat. That can mean tucking pants into socks and wearing long sleeves and hats. Long, flowy dresses should be checked carefully for ticks (or washed in hot water) if they’ve dragged on grass and should also be paired with leggings that are tucked into socks.

If you find a blacklegged tick attached to your body, pinch it close to the skin with forceps and gently pull it out. Put it in a plastic bag or pill container.

If you think the tick has been attached for a day or two, go to a health care provider and ask for the antibiotic doxycycline to prevent Lyme disease, Pritt said. Take the tick with you.

Whether or not you find a tick, watch for these symptoms:

- A fever during summer and spring, or, flu-like symptoms.

- Any rash you haven’t noticed before. Check out these pictures from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention for how the rash may look on different skin colors.

- A really bad headache.

- Any kind of joint aches and pains.

“It’s important to go to a doctor ASAP if you have any symptoms because something like Lyme disease doesn’t go away on its own–and it can get worse,” Pritt said. “Early treatment can prevent long-term complications.”

*CLARIFICATION: The story has been updated to clarify that while methods of controlling ticks in the field exist, such as applying pesticides, currently there isn’t widespread, effective use of any such methods.