Over the next few years, the oldest millennials will hit a major milestone. Welcome to

40 Is the New 40, a series of stories about—and for—a generation rethinking what it means to get older.

The one thing I knew about aging in my early 30s is that I for sure did not want to do any more of it. I was, after all, just starting the decade I’d been assured (by network sitcoms, beer ads, and men) would be my last on earth as a semirelevant human woman. As such, I had a lot to get done, including all the things I’d been deemed too young and unserious to do earlier in my life, like speak in uninterrupted sentences, get credited and compensated for my work, and relentlessly pursue dreams that did not require athleticism, decent health insurance, or disappointing anyone.

What would happen to me should I not achieve my full potential before the decade was up? I tried not to think about it too much, which was fine because men had already done the thinking for me. Just the act of turning 40, it seemed, would place me firmly on the wrong side of a series of binaries: young vs. ancient, promising vs. past expiration date, desirable vs. forest Wiccan with dried apricot vagina.

Oh, sure, I’d heard about some shadowy corners of the world where women over 40 supposedly “lived” and did “what they wanted,” but who was gullible enough to believe that? Not me, a person whose regular-degular life choices were so overscrutinized by strangers, politicians, and children that I wasn’t sure I even existed if I wasn’t being judged. Did I need to lose weight? Smile more? Lean in? Opt out? Have a family, a career, an aesthetically pleasing set of Kegel weights? Maybe. Still, I clung to the belief that being side-eyed was better than not being eyed at all.

“Say it again!” my therapist demanded the first time I admitted this out loud. We were both in our mid-40s by then, and her delivery was less psychoanalyst than slumber-party dare. I had barely gotten through “I was scared to turn 40 because invisibility” when we dissolved into laughter. How could something so inane have informed so much of my life? How had I, a brown woman with a reasonable amount of logic and deep familiarity with being ignored, come to frame aging as a private humiliation instead of just what happens when you don’t die? It was ludicrous. Preposterous! All the -ous! Later, after we had settled down, I whispered, angry with myself, “How did I really not know that this part would be so good?”

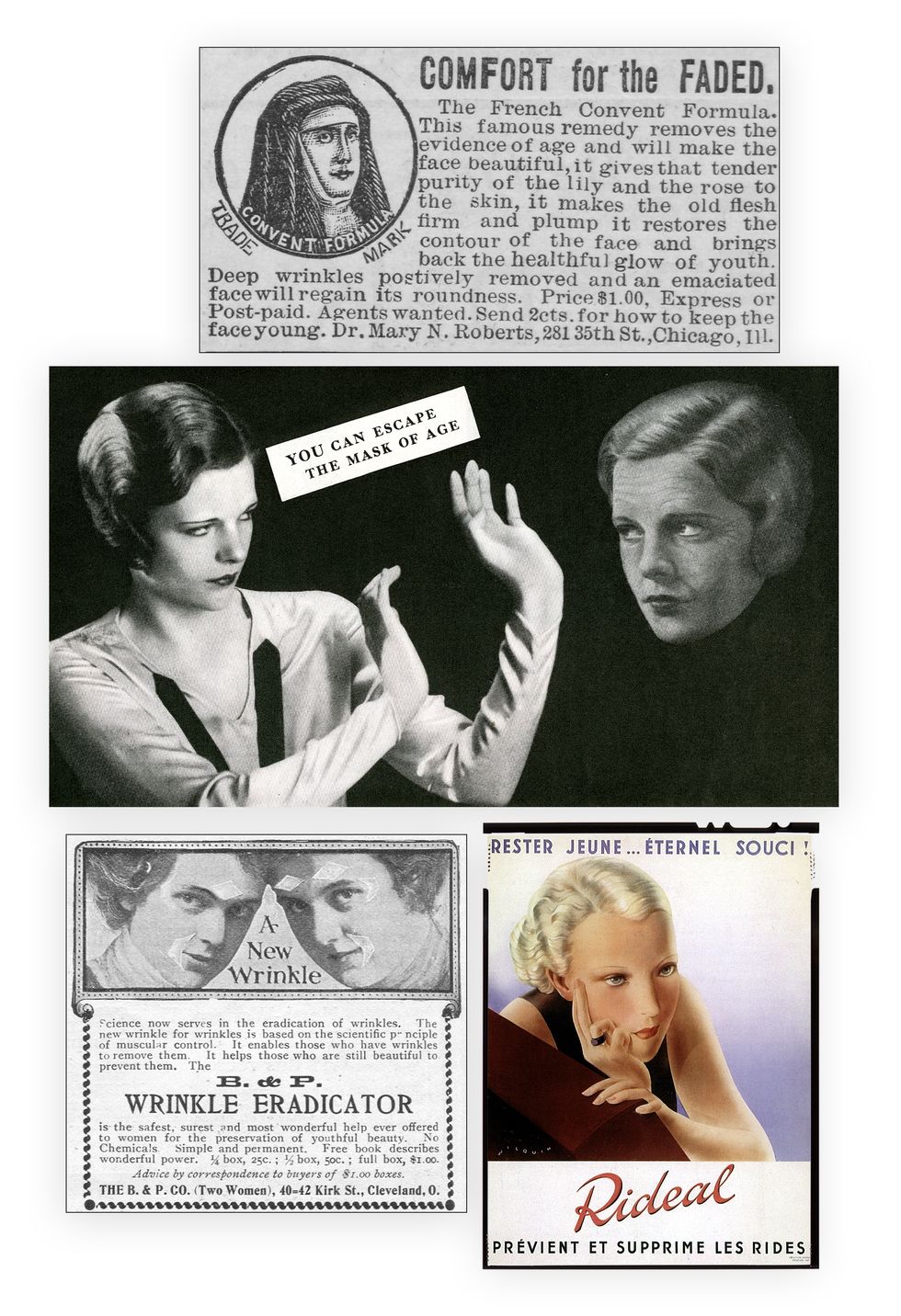

“Oh, girl, it’s by design,” my therapist said with a yawn, a sentence I have yet to fully recover from almost four years later because it’s so damning and true. Of course some insecure-as-hell system (looking at you, patriarchy!) decided the best way to permanently hobble women as a whole is to make sure we dread something natural and inevitable.

Can you imagine what we’d be capable of if we didn’t feel bad about aging? If we marched toward our 40s with the joy of a population who understood we were about to feel totally fine about ourselves? If we took for granted that other people’s criticism was and would always be the nipple hair of womanhood (ubiquitous, if unsettling) and decided that we were still going titties-free in the club?

The 40s, as it turns out, can be goddamn brilliant. They can be full of being your least cringing self, trying the things you were once scared to fail at, giving up on the shit that never felt great in the first place, and understanding that no one knows better than you what you should be doing with your mind, time, life, and body. They can be the moment you realize that anyone who tells you otherwise has a vested interest in keeping you small and scared.

Not to brag, but my 40s have been the decade I finally published my first book, had a quintuple orgasm, and lost my ability to see most of the pores on my face due to astigmatism. And not to keep not bragging, but they are also the decade I drew a second book, found a haircut that makes my head not look like toast, and perfected the art of leaving conversations that don’t deserve me.

Above all, they are the decade I have realized on a cellular level the following truth: There is not a network sitcom, beer ad, or man in the world who could even begin to predict the capabilities of a woman who realizes that she was always invisible to them—which means they were always irrelevant to her.