Unpacking a Box of Love

Fig. 1. Anonymous (18th century). Canivet (or devotional) (detail). Vellum, rose-colored paper, watercolor, 6 5/16 x 8 1/16 in. (16 cm x 20.5 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Mrs. Richard Riddell, 1981 (1977.627.17)

«From 16th-century religious devotionals to handmade tributes and the manufactured confections of today, the history of valentines is both long and vast. The objects and images that were created as valentines beautifully encapsulate the devotion, passion, love, and friendship felt by people across time and place.»

In last year's Valentine's Day blog post, I explored a very special form of valentine known as the cobweb: a complex cutwork device that was used to convey hidden images (fig. 2).

Fig. 2. Anonymous (American or British, 19th century). Cobweb valentine (animated GIF), 1830–40. Watercolor, cut tissue on board, diameter: 6 1/2 in. (16.5 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Mrs. Richard Riddell, 1981 (1981.1136.510)

This year, I would like to take you back to my own eye-opening introduction to the vast collection of valentines at The Met. It all started with one large black solander box, simply labeled "VALENTINES," which proved to be a true treasure chest (fig. 3).

Fig. 3. Solander box filled with historic valentines from The Met collection

Once I opened the elegant box, I immediately took an intimate tour of its lush content, which, as it turns out, forms a perfect introduction to the art, beauty, and historic evolution of the valentine.

Fig. 4. Canivet (or devotional). (1977.627.17)

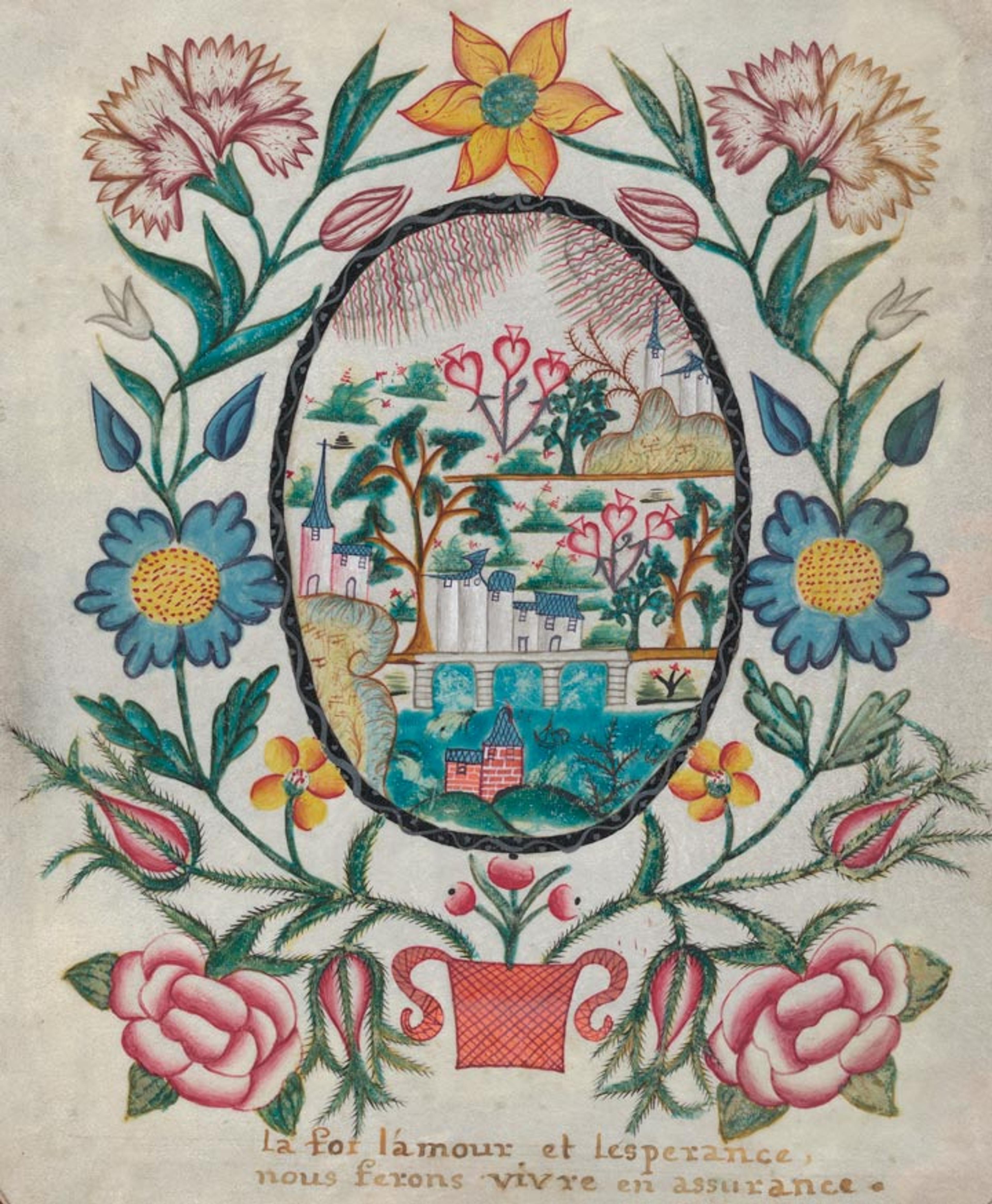

The first object from the box is not a true valentine, but illustrates one of its predecessors (fig. 4). Known as so-called canivets or devotionals, these consisted of religious imagery on parchment, often decorated with cut-work ruffles and flowers. They were meant to be given as gifts to commemorate a birth, death, birthday, communion, marriage, or simply to express love. Gradually devotionals evolved to become romantic missives, and many of the religious elements became secular. Sacred hearts became the hearts of lovers, and eventually parchment was replaced by commercial cameo-embossed, openwork lace paper.

Fig. 5. Anonymous (French, 18th century). Early valentine, or lover's gift, ca. 1750–1800. Vellum, hand painted, 3 15/16 x 8 7/8 in. (22.5 x 10 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Mrs. Richard Riddell, 1984 (1984.1164.69)

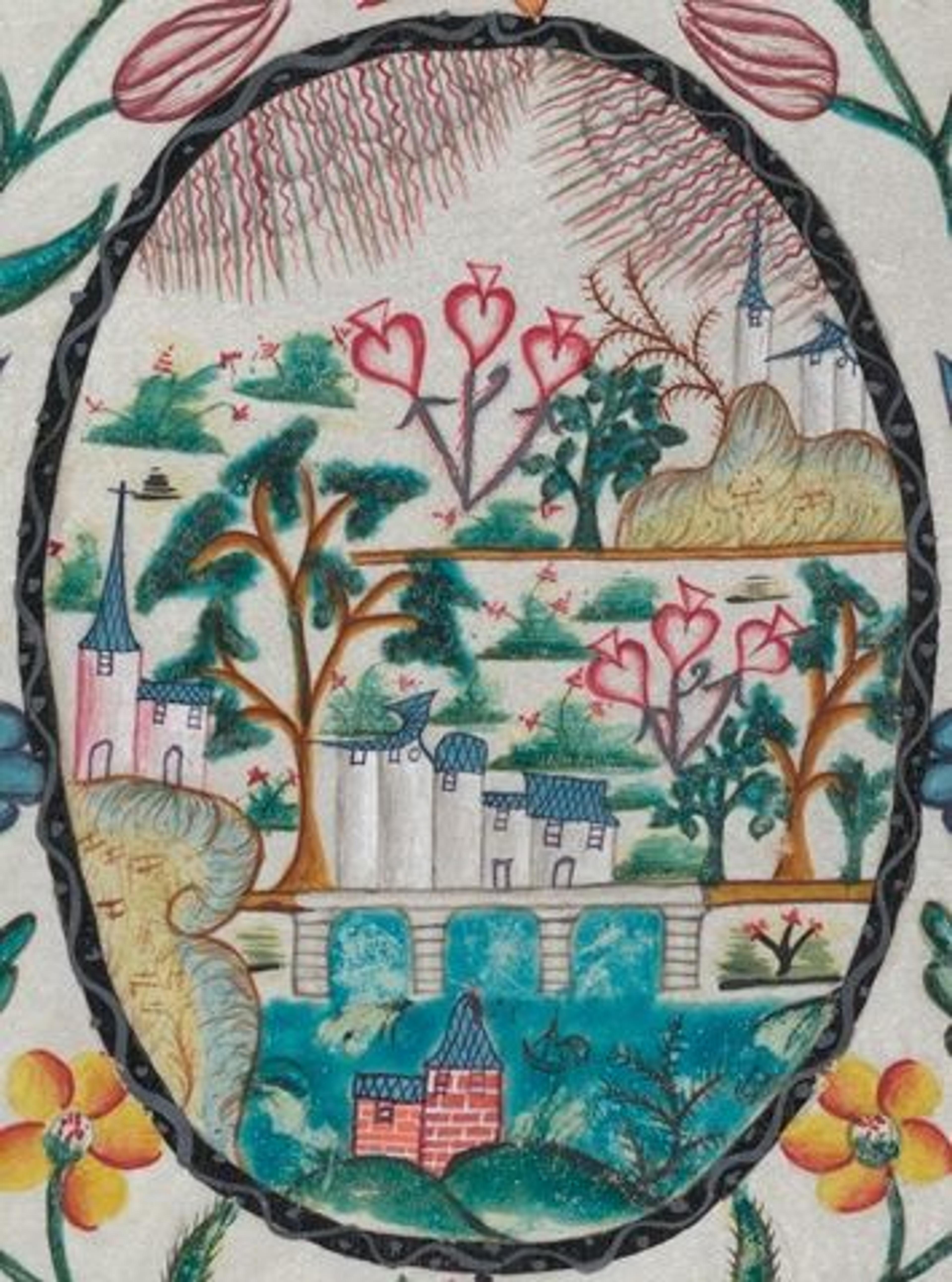

This exquisite French parchment masterpiece from the 18th century shows a subsequent step in the evolution from devotional to valentine (fig. 5). Its painted and pinpricked decorations consist of several layers of meaning. The flowers, which surround the central oval medallion, are poetic, for both the rose and the carnation symbolize love. The scene within the central medallion depicts a stormy sky above a medieval village (fig. 6).

Left: Fig. 6. Detail of the early valentine (1984.1164.69)

There are castles, an aqueduct or bridge, and even a boat on a tranquil lake. The trees in this magic land grow hearts. The village is thriving, despite the storm raging above. This imagery, in combination with the inscription below—which translates as "Love and Hope will keep our lives secure"—might suggest that this missive was meant as a proposal of marriage, a thought strengthened by the inclusion of a church, the place where marriages are sanctified.

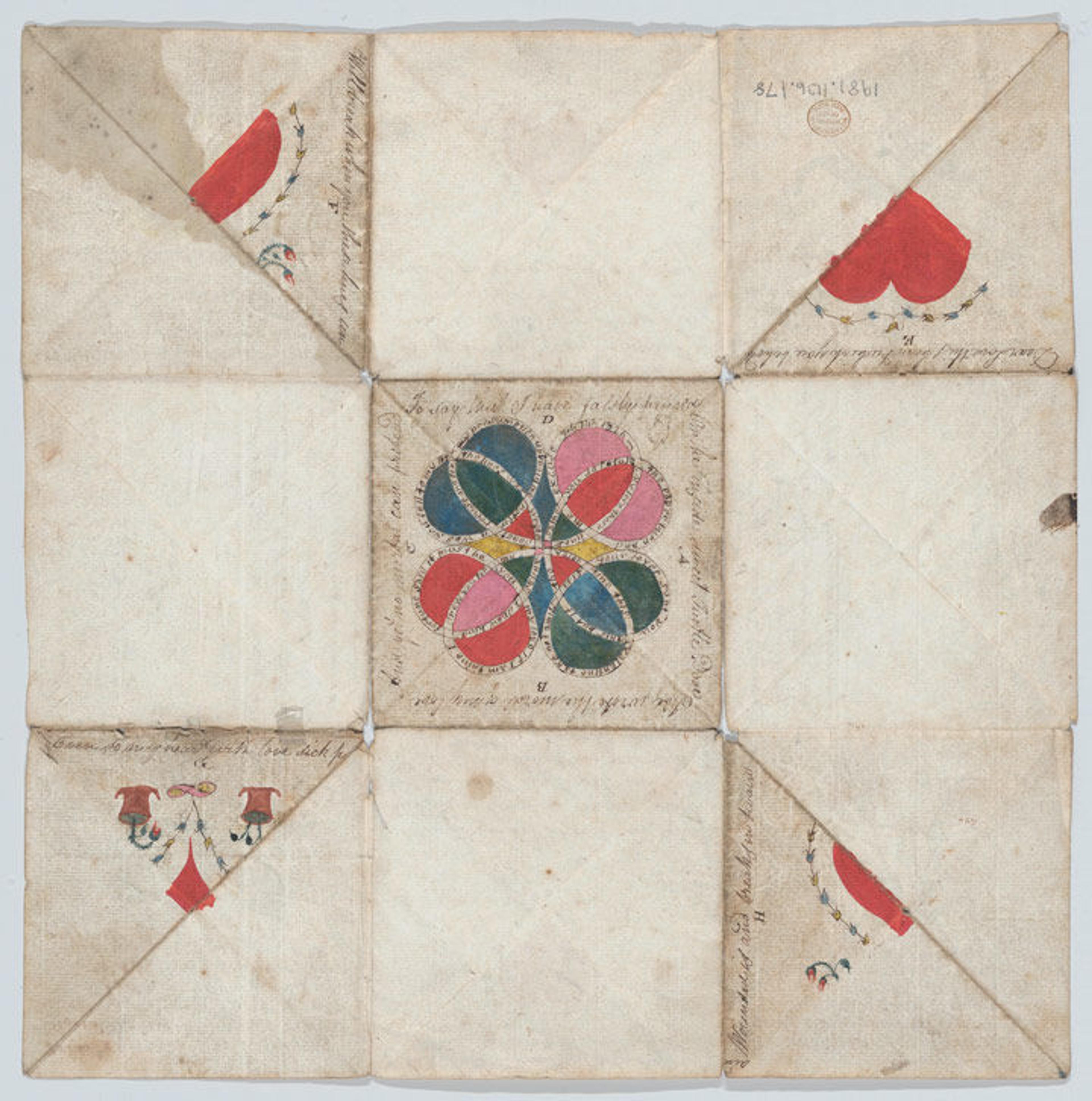

During the 18th and 19th centuries, the puzzle purse was another coveted handmade gift. These paper treasures, made out of intricately folded sheets of paper in a manner not unlike origami, were used as a playful way to convey a message, but could also contain a gift. They were used as early baptismal certificates and the folded packet might then contain a coin as a baby gift. When used as a valentine they could include a lock of hair, a ring, or a lover's promise.

Fig. 7. Anonymous (British, 19th century). Valentine: Puzzle purse (verso), 1826. Paper, watercolor, gold paint, 12 5/8 x 12 3/16 in. (32 x 31 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Mrs. Richard Riddell, 1981 (1981.1136.178)

The exterior of this puzzle purse from The Met collection, dated February 14, 1826, shows how the sheet would be folded in nine squares and then further into triangular shapes (fig. 7). Each square would be decorated with drawings or poetry and then numbered to indicate the order in which the message was to be read once the recipient opened the purse.

Fig. 8. Detail views of the puzzle purse (1981.1136.178)

The purse would arrive closed, and the first thing the recipient would see was the central square of the exterior decorated with an "Endless Knot of Love" (fig. 8, left). The poetry surrounding it was numbered alphabetically so that it could be read in proper order:

On the inside sweet Turtle Dove

I've wrote the moral of my love

And yet no mortal can pretend

To say that I have falsely penned

The interior central square shows two hearts fused together combined with baskets of flowers, and the interlinked initials of the two lovers in gold paint (fig. 8, right). The eight squares surrounding it reveal a complex language of text and images, which convey the sender's hope that the hearts of the two lovers might be joined together or suggests that if the love is unrequited, the recipient should burn the valentine (fig. 9). The fact that this puzzle purse is now in the Museum's collection thus suggests a happy ending!

Fig. 9. Anonymous (British, 19th century). Valentine: Puzzle purse (recto), 1826. Paper, watercolor, gold paint, 12 5/8 x 12 3/16 in. (32 x 31 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Mrs. Richard Riddell, 1981 (1981.1136.178)

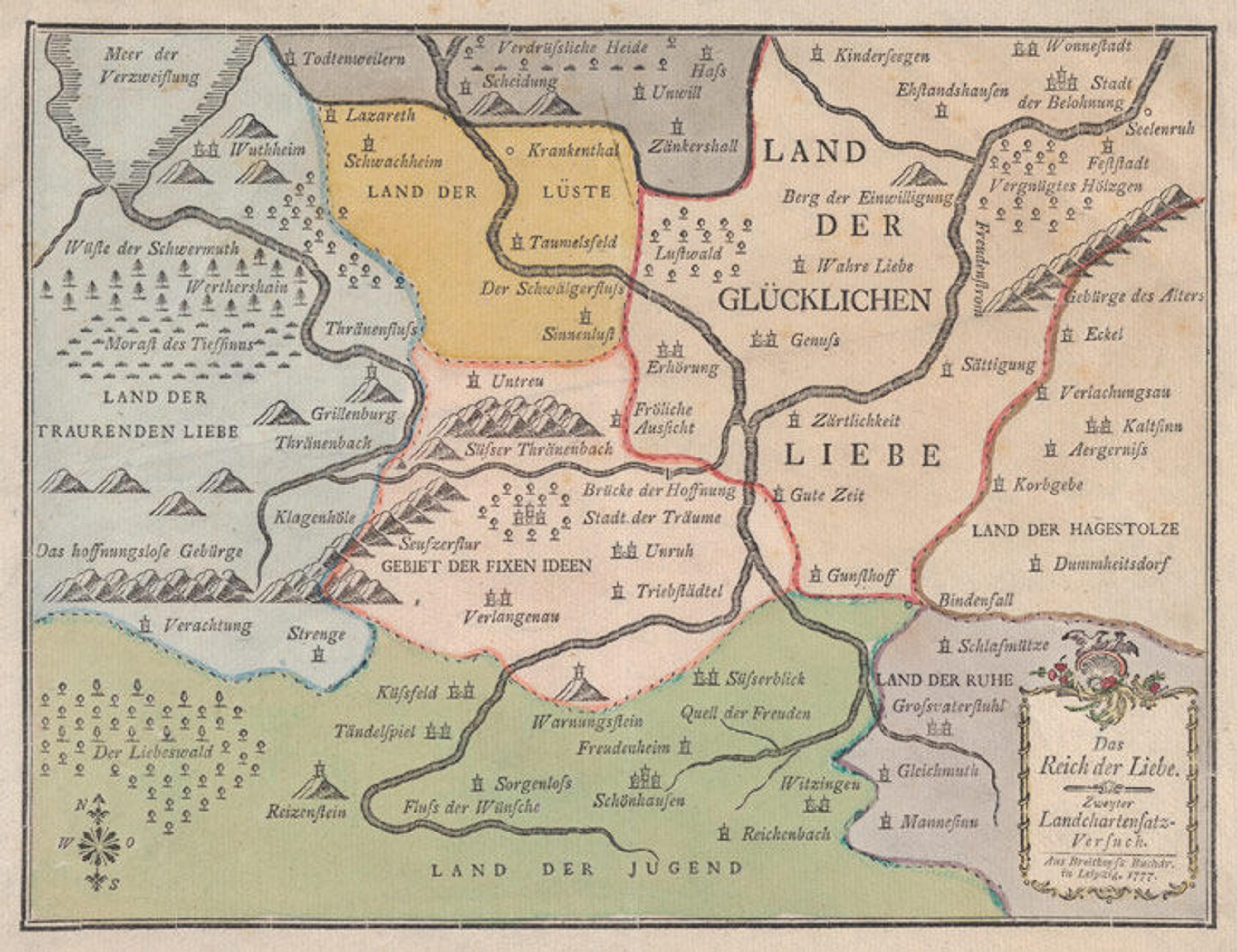

Another unexpected form of valentine actually looks more like the work of a cartographer. From the 18th century onward, when the commercial print industry started to get involved in the celebration of the Feast of Saint Valentine, maps with themes of matrimony and love became popular. Printed in 1777 by Breitkopf in Leipzig, Germany, the map below situates Das Reich der Liebe (The Kingdom of Love) amid the "Land of the Happy," the "Land of Lust," the "Land of Youth," and, alas, also the lands of "Mourning Love" and "Fixed Ideas" (fig. 10).

Fig. 10. Published by Breitkopf & Härtel (German, 18th century). Valentine: Map of the Kingdom of Love (Das Reich der Liebe), 1777. Printed on paper from type composition, hand colored, 11 7/16 x 9 1/16 in. (29 x 23 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Mrs. Richard Riddell, 1981 (1981.1136.110)

One of the most exciting finds during my first viewing of that black treasure box in the collection was a very special card by the "Mother of the American Valentine,” Esther Howland (1828–1904). Until the middle of the 19th century, the American valentine industry was far behind on European production and depended greatly on luscious imports from England and France. Esther Howland was one of the first entrepreneurs in the United States to popularize the lace-paper valentine.

Fig 11. Attributed to Esther Howland (American, 1828–1904). Lace paper valentine, ca. 1855. Cameo-embossed lace paper, chromolithographed die-cuts, faux pearls, blue satin, white satin ribbon, gold paper stars, graphite, 9 1/8 x 7 7/8 in. (23.2 x 20 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Mrs. Gladys Norbury, 1957 (57.565)

Howland's early products can be identified through distinct marks, either a red letter H, or an embossed stamp that reads "NEV Co," which stands for New England Valentine Company. The Met has many of these signed pieces in the collection, which help us to identify the distinct features of Howland's work and allow us to attribute unmarked examples, like the one found in the black box, to her hand as well.

The card above may be considered as a tour de force and reflects the pinnacle of the valentine as a magical lace-paper confection. Its base is formed by fancy lace paper manufactured by the English firm Mansell. This delicate, cameo-embossed, open-work paper was often used by Esther Howland. Numerous delicate lift-up lace flaps—one of her trademark designs—add to the spectacular creation, until the image of a loving couple is finally revealed (fig. 12). The blue satin insert and white ribbons with gold stars and pearl drops are other signature embellishments.

Fig. 12. Animated GIF of the lace paper valentine's additional layers being revealed (57.565)

The reverse of one of the interior flaps contains an inscription in graphite: "Elizabeth Rowe Bogert from Augustus Bogert." The latter was a well-known New York wood engraver who created illustrations for Harper's magazine and various other books, many of which can be found in museum collections today. In 1850, he married Elizabeth Rowe and, as a successful artist, could afford a luxurious valentine such as this one, which would have cost up to the equivalent of 50 dollars at a New York stationer.

This last treasure from the black box illustrates perfectly how each valentine has a unique story to tell. The range of objects, from the unique and handmade to the commercially produced and store-bought, is a fascinating indication of the significance given to the festive holiday of Saint Valentine. At The Met, we conserve these "fingerprints of love" for future scholars, collectors, and lovers to study and enjoy.

Nancy Rosin

Nancy Rosin is a volunteer cataloger in the Department of Drawings and Prints.