Paper Pastimes: Puzzles, Games, and Other Creative Outlets from the Collection of Drawings and Prints

From left: "Tethers"; "King of Tethers"; "Queen of Collars", ca. 1475–80. From The Cloisters Playing Cards. South Netherlandish. Paper (four layers of pasteboard) with pen and ink, opaque paint, glazes, and applied silver and gold, each: 5 3/16 x 2 3/4 in. (13.2 x 7 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, The Cloisters Collection, 1983 (1983.515.1–.52)

It is a little-known fact that The Met is the keeper of many historic puzzles, games, and other popular pastimes. Because they have formed a significant category within the graphic arts since the wide-spread introduction of paper in the late fourteenth century, a vast selection can be found in the Department of Drawings and Prints. While our interest in them may have waned slightly over the past few decades, they have recently taken on a renewed relevance.

The "new normal" of working from home during the Covid-19 shelter-in-place measures has urged many to reassess how they spend their free time. Instead of going out, our social stomping grounds have been reduced to the couch and kitchen table. In an effort to not be glued to the screen 24/7, my partner and I raided the shelves of a nearby store and stocked up on more jigsaw puzzles and board games than either of us had touched in the last decade. In doing so, I have developed a much deeper appreciation for how important such amusements were for people’s sanity in the days before television and the internet.

Decks of playing cards, in particular, hold an important place in the history of printing as they were among the first commercial applications of the novel techniques of woodblock and intaglio printmaking. Luxury hand-drawn decks, like the ones seen above, were produced during this early period as well (although they were not used in everyday play, if at all). The quality of their printed counterparts could vary immensely, from crudely-cut and quickly-printed woodcut images to sophisticated engravings with imaginative suits and custom card shapes.

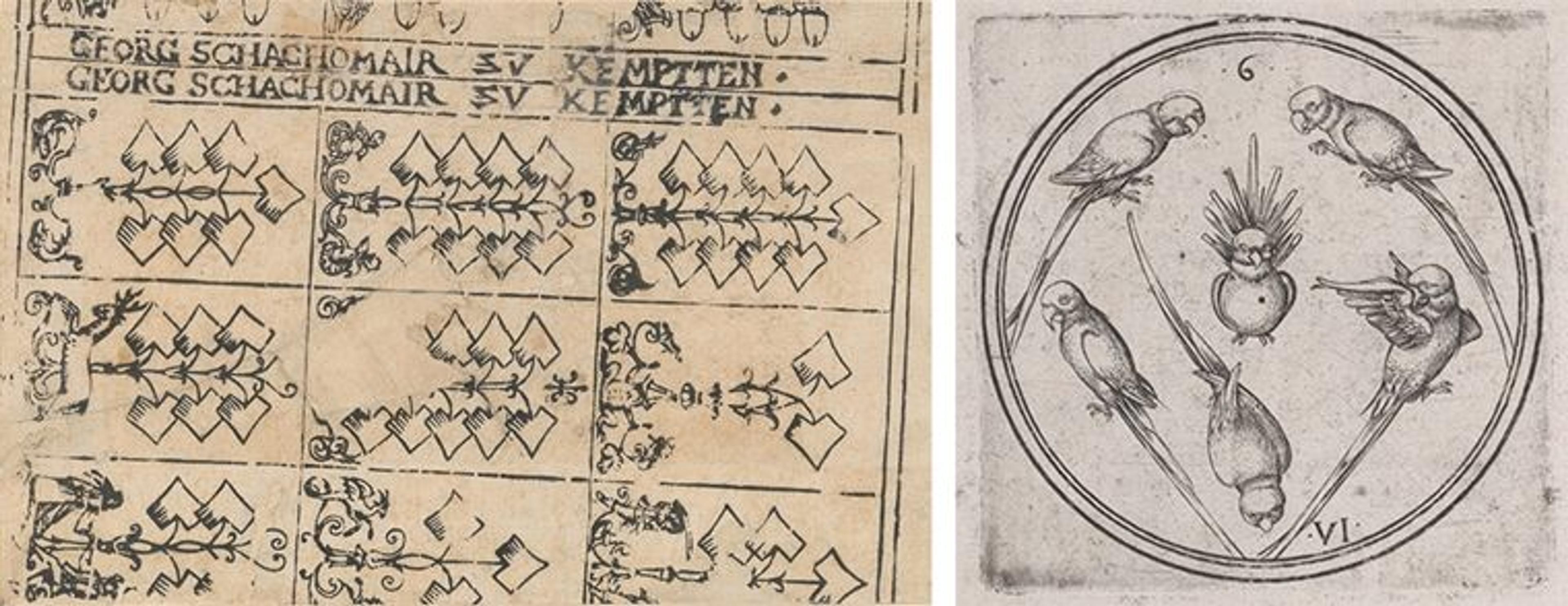

Left: Georg Schachomair (German, 16th century). Sheet of uncut playing cards, 1575–1600. Woodcut, 12 3/8 x 7 15/16 in. (31.4 x 20.1 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, The Elisha Whittelsey Collection, The Elisha Whittelsey Fund, 1949 (49.95.271) | Right: Master PW of Cologne (German, active Cologne, ca. 1490–1515). The Six of Parrots, from the series of round playing cards, ca. 1500. Engraving, 5 1/4 x 7 3/16 in. (13.3 x 18.3 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, The Elisha Whittlesey Collection, The Elisha Whittelsey Fund, 2018 (2018.865)

Playing cards are just one of a wide variety of paper pastimes to be found in our collection. My colleagues in the Department of Drawings and Prints and I would like to share few of our favorite examples. Many will be familiar to you and may even line the shelves of your cupboard, attesting to their universal appeal across time and space.

— Femke Speelberg, Associate Curator

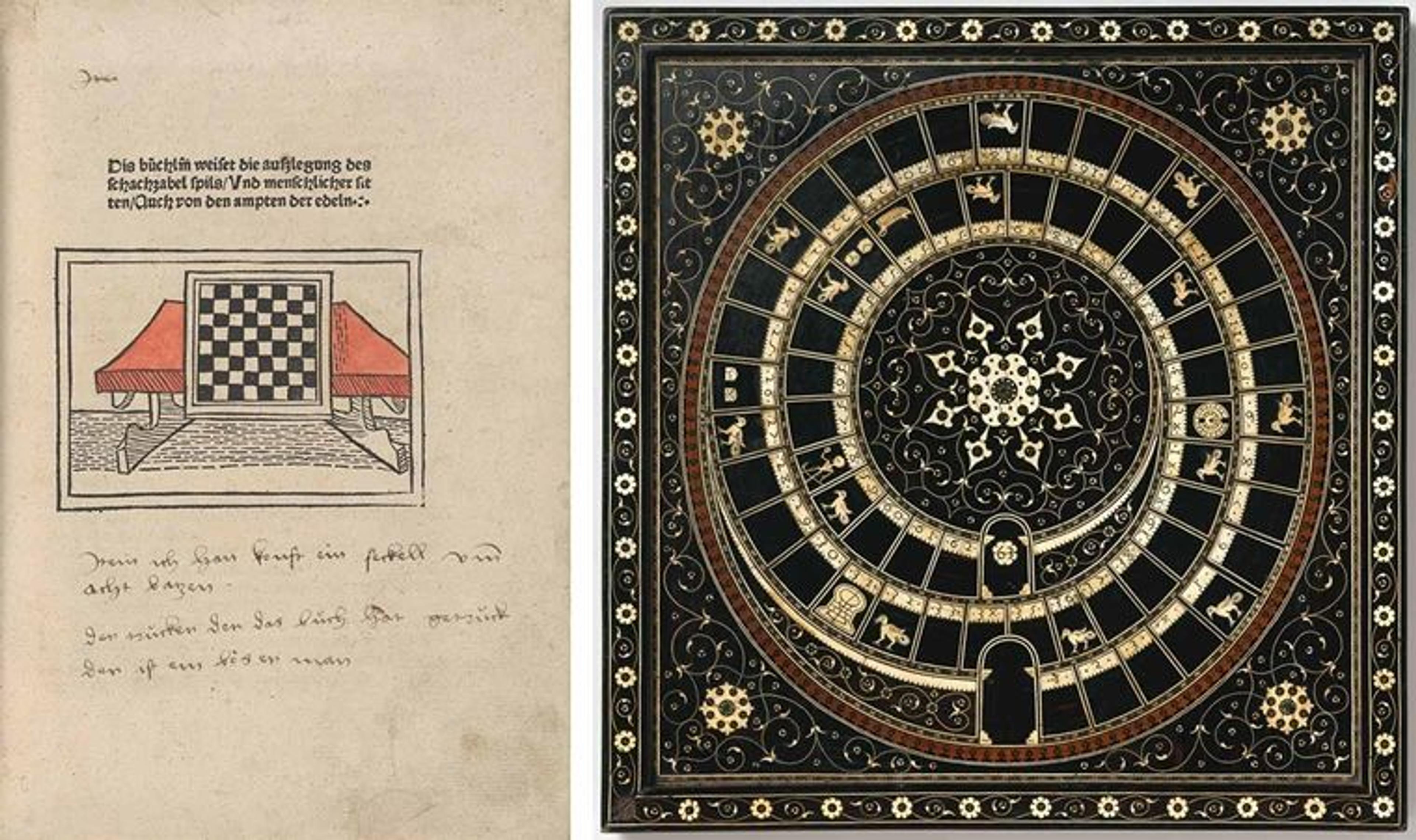

Board games

Left: Jacobus de Cessolis (Italian, active 1288–1322), The Book of Chess, 1483. Woodcuts with letterpress, touches of watercolor, 11 1/8 x 8 1/16 x 7/16 in. (28.3 x 20.5 x 1.1 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Pfeiffer Fund, 2017 (2018.80) | Right: Chess and goose game board, late 16th century. India, Gujarat. Ebony, ebonized wood, ivory, horn, gold wire, 1 1/8 x 16 ½ x 16 15/16 in. (2.9 x 41.9 x 43 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Pfeiffer Fund, 1962 (62.14)

The modern game of chess developed in Southern Europe during the late Middle Ages, from versions of an Indian game called chaturanga. The game was described in the thirteenth century by the Dominican friar Jacobus de Cessolis, who not only explained the rules of the game, but used the ranks of the chess pieces to reflect upon the moralities within society. The book gained great popularity, and was translated into many languages. The first printed editions were published in the 1470s, and the English merchant William Caxton’s adaptation, called The Game and Playe of the Chesse, even represented one of the first books to be printed in the English language. Chess was not the only board game to be played during this early period, however. The luxurious example above combines the game of chess with another popular boardgame: the so-called Game of the Goose, of which many cheaper versions were printed on paper.

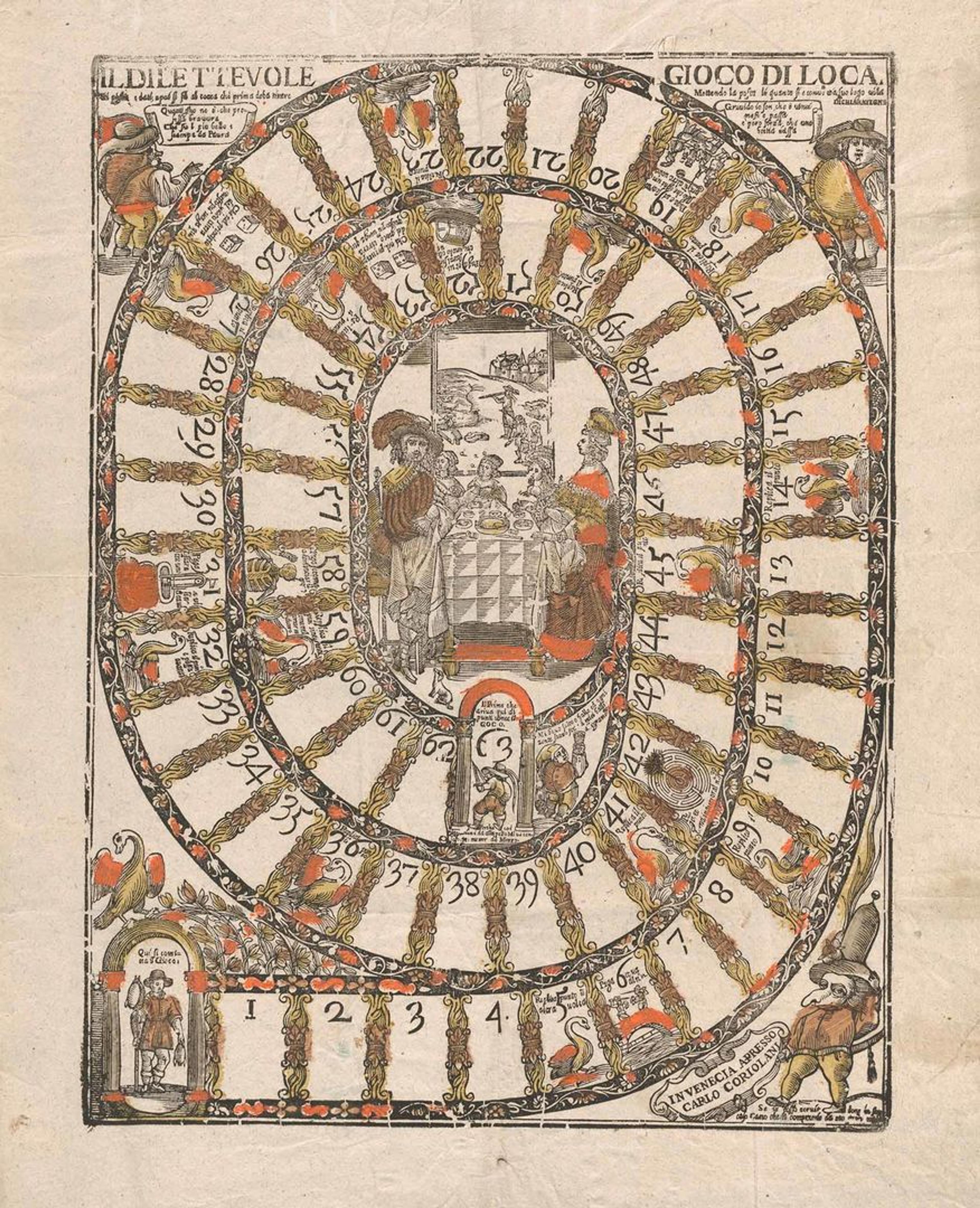

The Game of the Goose seems to have originated in Italy in the late fifteenth century, and quickly became one of the most popular board games across the world. Its basic form has changed little since the time it was invented. Because it is a game that requires no skill, it is played by children and adults from every echelon of society. Participants throw dice to move their piece from the outside of the spiral track to the middle. There are hazards along the way: for example, square 58 is the "square of death," and if you land there you are sent back to the beginning. Other squares help the player; those marked with a goose send you forward by the amount rolled on the dice. To win the game, the piece must land exactly on square 63. The boards can be given different themes, and their designs are often intricate and beautiful, revealing considerable artistic imagination. Many refer to politics or social concerns of the day.

The Pleasant Game of the Goose (Il Dilettevole Gioco di Loca), published by Carlo Coriolani, Venice, after 1640 (probably late 17th century). Woodcut with contemporary hand coloring, 23 1/4 x 18 5/16 in. (59 x 46.5 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, The Jefferson R. Burdick Collection, Purchase, Jefferson R. Burdick Bequest, 2016 (2016.215)

This Italian example, titled The Pleasant Game of the Goose, includes a central scene of people dining, and recognizable characters from popular culture in each of the corners. Color was added by hand to enliven the game board.

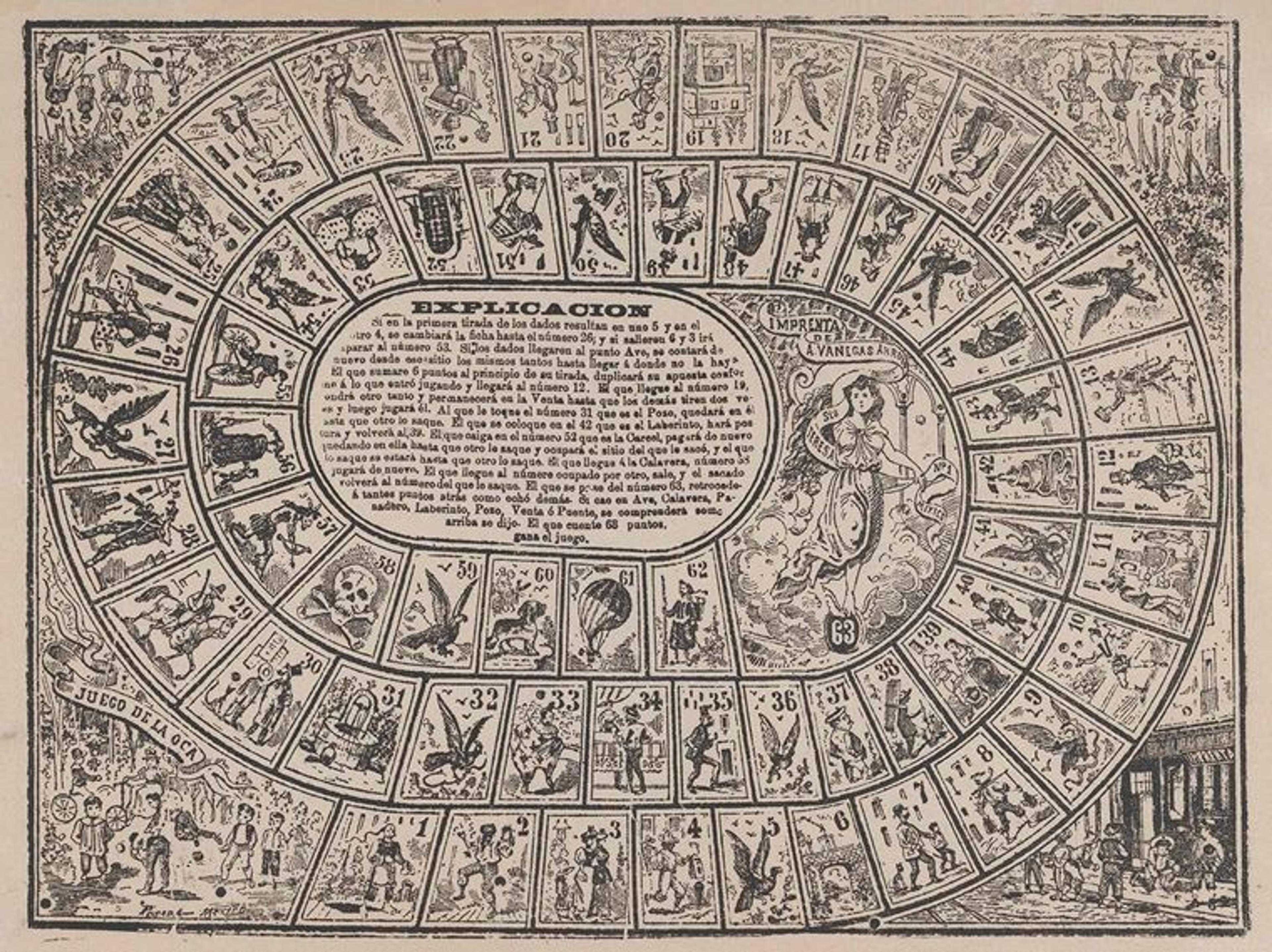

The example below, designed over 200 years later by the well-known Mexican artist José Guadalupe Posada, includes instructions in the middle and vignettes of children playing around the edges.

José Guadalupe Posada (Mexican, 1851–1913). Game of the Goose, ca. 1900¬–1910. Photo-relief and letterpress on buff paper, 12 x 15 3/4 in. (30.5 x 40 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, The Elisha Whittelsey Collection, The Elisha Whittelsey Fund, 1946 (46.46.304)

Picture and Word Games

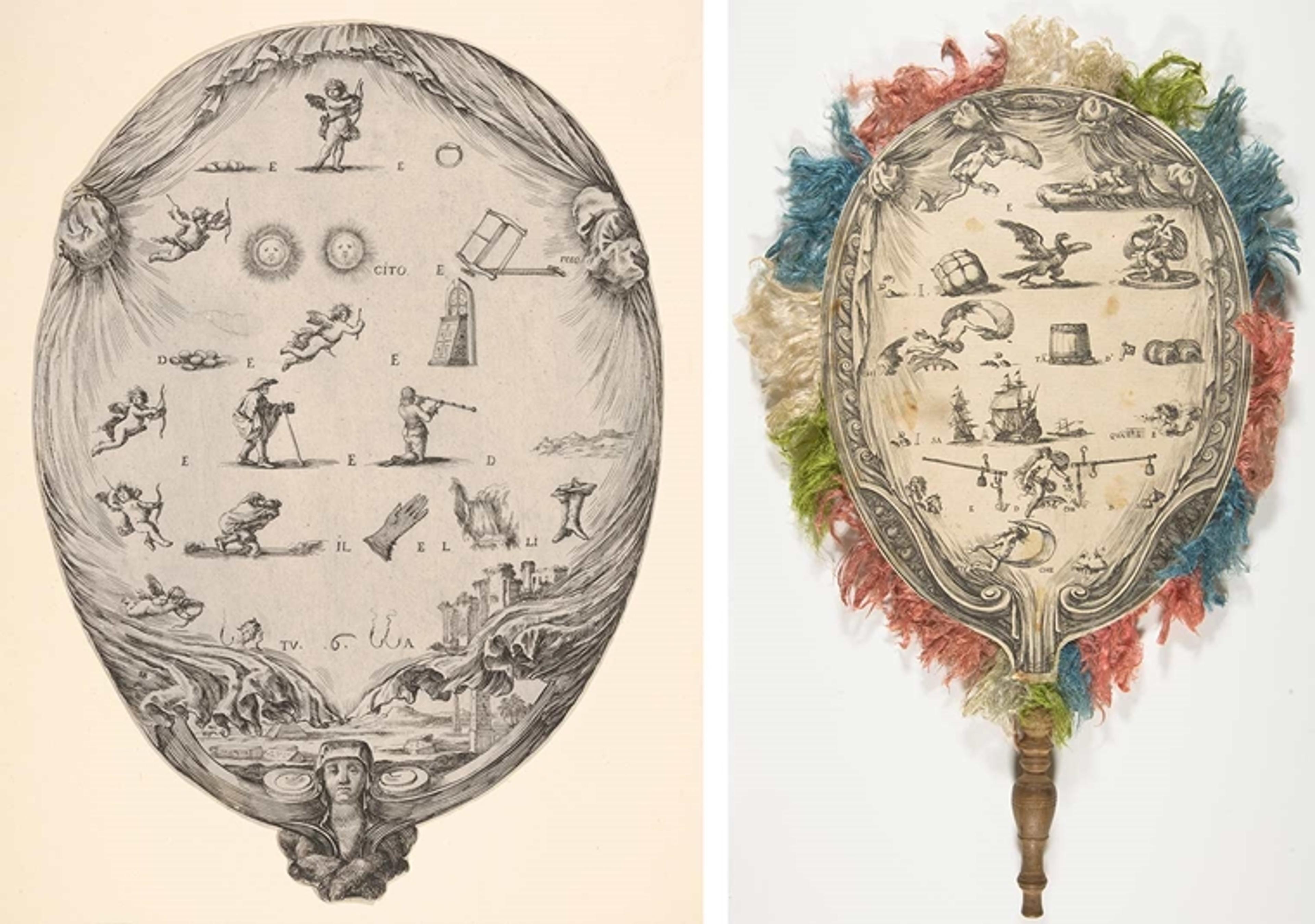

Left: Stefano della Bella (Italian, Florence 1610–1664 Florence). Rebus on the subject of love, ca. 1637–42. Etching, 11 3/16 x 10 1/16 in. (28.4 x 25.5 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Bequest of Phyllis Massar, 2011 (2012.136.432.2) | Right: Stefano della Bella (Italian, Florence 1610–1664 Florence). A fan with a rebus on Love on one side Fortune on the other, after ca. 1637–42. Etching, with fringe around the edges and a wooden handle. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Estate of Florance Waterbury, 1970 (1970.610)

In the seventeenth century, the Florentine artist Stefano della Bella created two prints with rebuses, language puzzles that use illustrations to depict words or phrases. He used a range of images to convey messages about love and fortune. In many cases, the images do not literally represent the hidden words. But once they are sounded aloud, the puzzler can hear the meaning of the covert communication. Della Bella’s prints are doubly useful, as he fashioned them in the form of fans. The Museum owns a rare example of how these prints could be mounted together to form a double-sided fan (in this instance, affixed to a turned wooden handle and decorated with a colorful fringe edge). Now portable, the games could be taken out into the garden or to a social gathering to be solved in the company of friends and family.

Lussano (Italian(?), active ca. 1794), after Christian Schwan (German, active 18th century). Hidden silhouettes of the rulers of Europe, 1794. Etching, 8 9/16 x 12 3/8 in. (21.7 x 31.4 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, The Glenn Tilley Morse Collection, Bequest of Glenn Tilley Morse, 1950 (50.602.203)

Hidden silhouettes were another game that lent themselves well to covert messaging. The artist who designed the above picture of a landscape with a funerary monument also hid within it the silhouettes of various rulers of Europe. In this case, the puzzler is helped by the inscription below, which details whose likeness to look for. However, this information is often not given so readily. Especially in the late eighteenth-century, when Europe was caught in the political upheavals of the French Revolution and its aftermath, hidden silhouettes were often employed to spread imagery of royal families to loyal monarchists.

Paper Cutouts

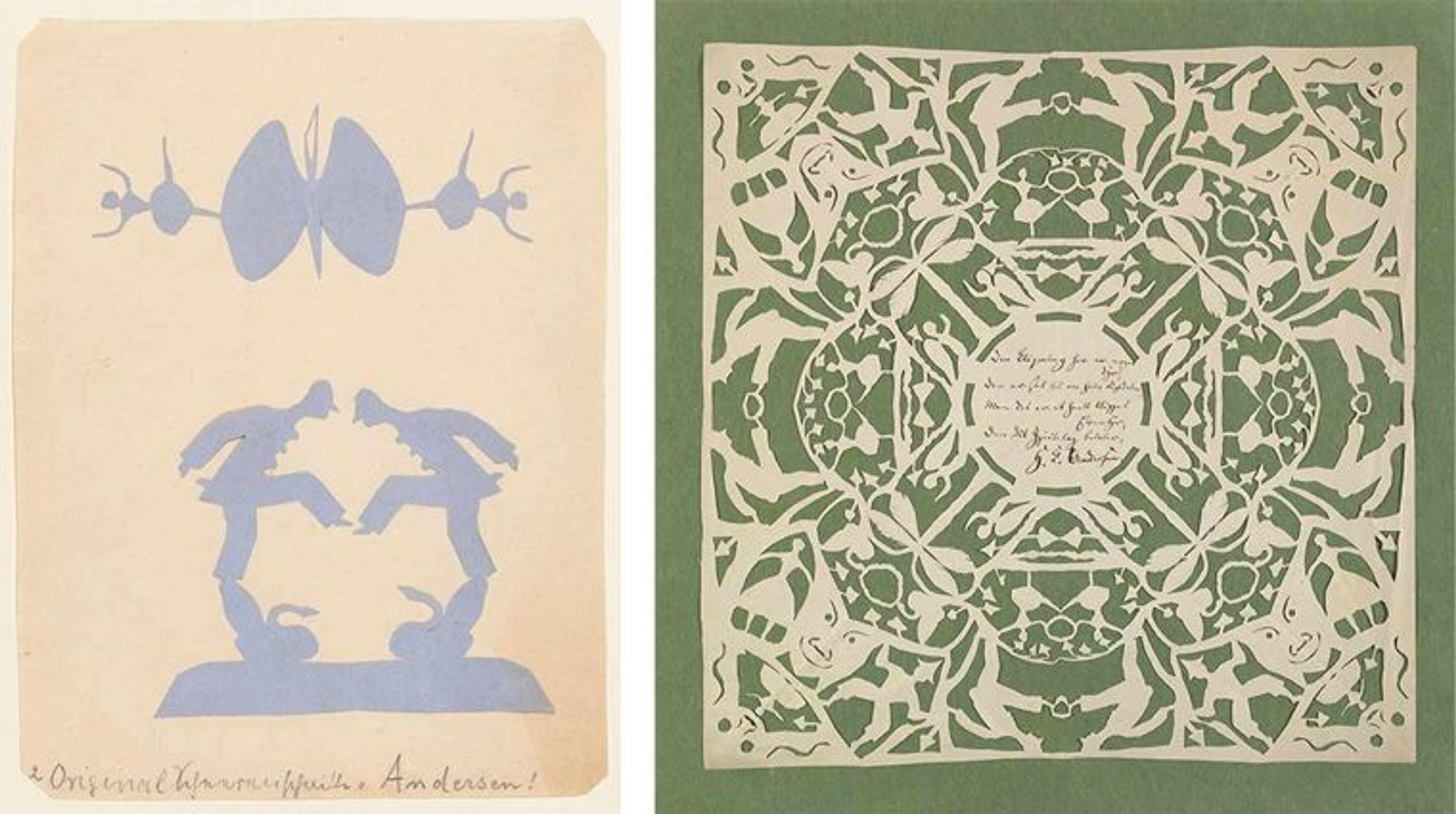

Left: Hans Christian Andersen (Danish, Odense 1805–1875 Copenhagen). Two Pierrots Balancing on Swans and Two Dancers, 1820–75. Cutout in blue paper, mounted on an album sheet, 6 7/16 x 4 7/8 in. (16.4 x 12.4 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Mary Martin Fund, 2003 (2003.384) | Right: Hans Christian Andersen (Danish, Odense 1805–1875 Copenhagen). A Fully Cut Fairy Tale, ca. 1864. Paper cutout mounted on a green sheet, 13 9/16 x 13 14 in. (34.4 x 33.7 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, The Elisha Whittelsey Collection, The Elisha Whittelsey Fund and Mary Martin Fund, 2012 (2012.379)

Paper cutting was a popular means of image-making throughout the nineteenth century. Anyone with access to paper and a pair of scissors could engage in the art of the cutout. The Museum has several examples from one of the medium’s most famous practitioners: Hans Christian Andersen (1805-75), author of The Little Mermaid, The Emperor’s New Clothes, and The Ugly Duckling. Andersen had a penchant for entertaining his friends and their families by creating paper cuttings as he narrated fairy tales. Those who witnessed it noted the excitement they experienced when Andersen finally opened a folded sheet to reveal interlocking patterns composed of the silhouettes of dancers, swans, mermaids, and other subjects found in his books. Andersen often repurposed the cutouts, adhering them to the pages of albums—which he also filled with clippings of book and newspaper illustrations—that he gifted to the children of his friends. He lent his paper cutting talents to fundraising efforts, as well, using the funds from the sale of A Fully Cut Fairy Tale, an intricate and complex composition pasted to a green sheet (illustrated above), to support the relatives of fallen Danish soldiers during the Second Schleswig War of 1864.

Paper Construction

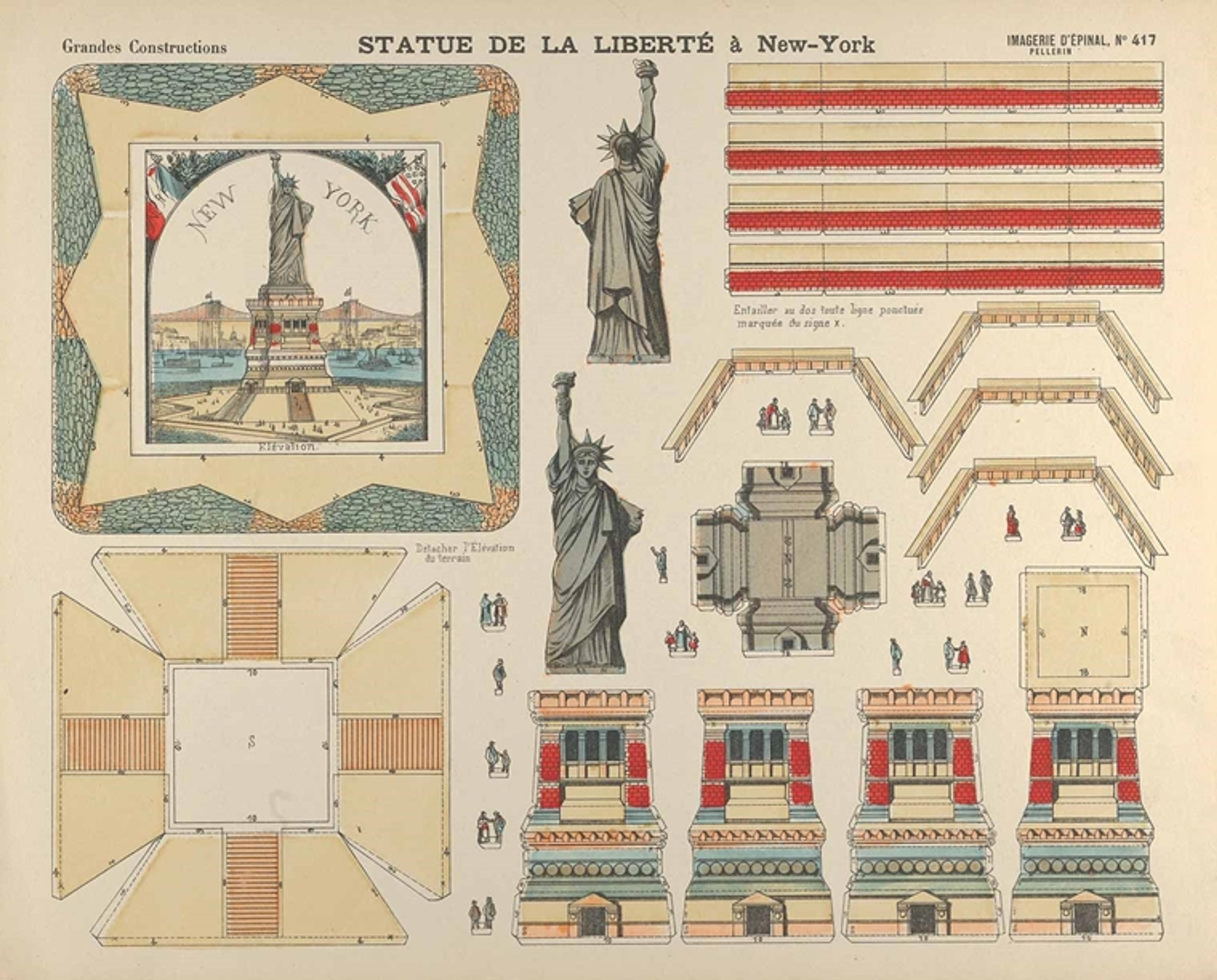

Imagerie d'Épinal, Pellerin & Cie. (French). The Statue of Liberty, no. 417 from Grandes Constructions, 1880–1900. Lithograph with hand-coloring, 15 3/8 x 19 3/8 in. (39 x 49/2 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of D. Lorraine Yerkes, 1962 (62.645.53)

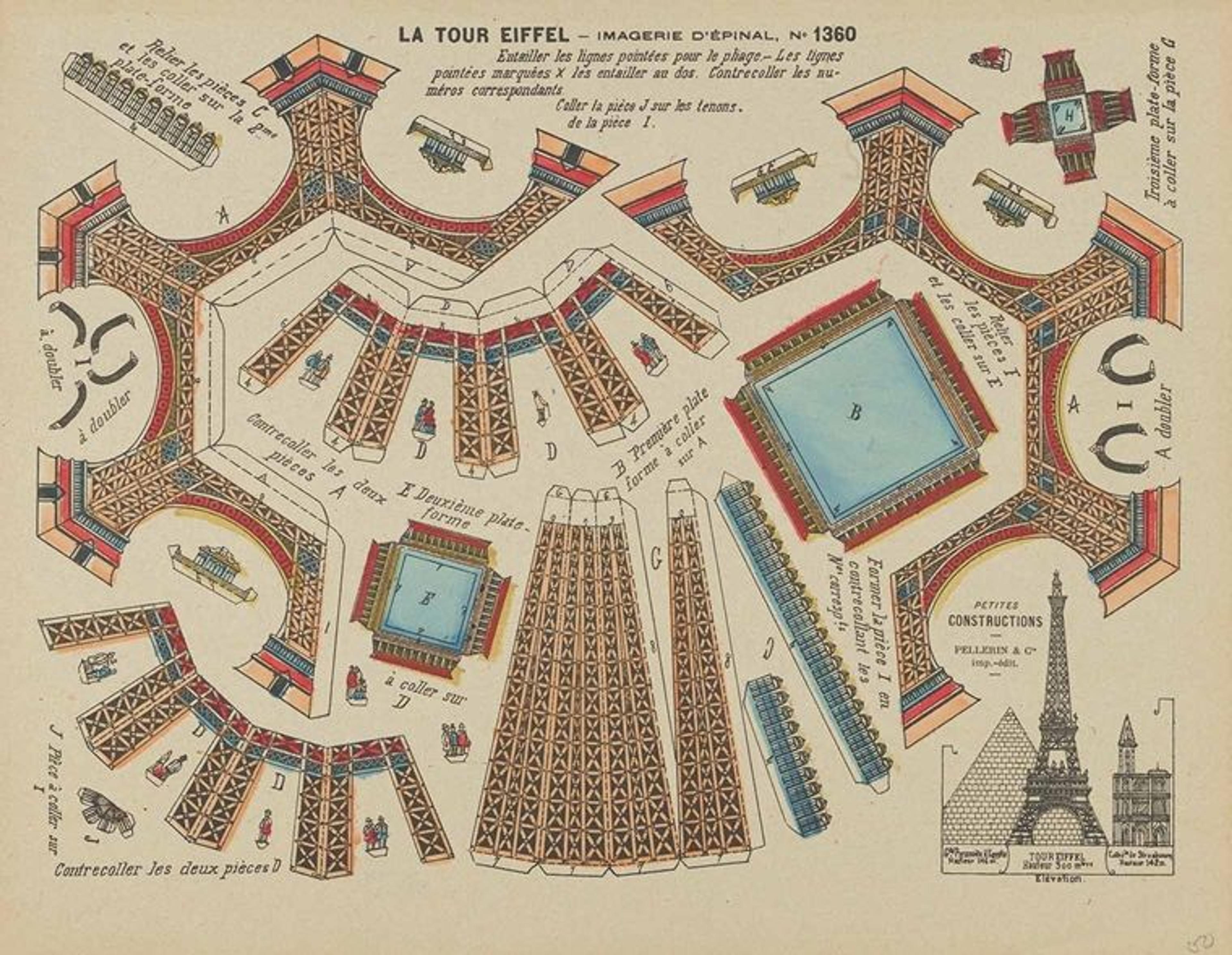

Some prints for passing time were meant to be cut up and then reassembled, like this nineteenth-century lithograph of the Statue of Liberty published by the prolific workshop of Imagerie d'Épinal, Pellerin & Cie. Originally a producer of playing cards and religious keepsakes, Pellerin expanded its audience to include the new market of children by printing sheet music, games, stories, and paper constructions. The "Petites" and "Grandes Constructions" were marked with lines to indicate cuts and folds and numbered tabs to match and glue together. Here the base in the upper left corner, also to be cut out, provides an image of the completed design. Subject matter varied from landmarks to styles of architecture to fairy tales. The sophisticated illustrations and delicate details such as the tiny tourists suggest that these prints would appeal to adults and children alike. The Eiffel Tower (seen below), once assembled, would bring a tiny part of Paris into your home, which, in the era of quarantine and social distancing, sounds like a dream come true!

Imagerie d'Épinal, Pellerin & Cie. (French). The Eiffel Tower, from the Petites Constructions, no. 1360, 1880–1900. Lithograph with hand-coloring, 9 1/16 x 11 13/16 in. (23 x 30 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of D. Lorraine Yerkes, 1962 (62.645.9)

Femke Speelberg

Associate Curator Femke Speelberg joined the Department of Drawings and Prints in 2011 and is responsible for ornament and architectural drawings, prints, and modelbooks. Her work focuses on the history of design and the transmission of ideas. Femke's research is inherently interdisciplinary, connecting works on paper with artworks, objects, and architecture from the fifteenth to the twentieth century. She often collaborates with other Museum departments on installations and publications. She has curated the exhibitions Living in Style: Five Centuries of Interior Design from the Collection of Drawings and Prints (2013) and Fashion and Virtue: Textile Patterns and the Print Revolution, 1520–1620 (2015).

Mark McDonald

Allison Rudnick

Associate Curator Allison Rudnick manages the Study Room for Drawings and Prints and oversees the ephemera collection. She joined the department as a research assistant in 2012 and has held positions at the print shop Harlan & Weaver and the Whitney Museum of American Art. Active in the field of contemporary printmaking, she is a frequent contributor to Art in Print and serves as treasurer for the Association of Print Scholars. She holds a BA from Connecticut College and an MPhil from the Graduate Center of the City University of New York, where she is a PhD candidate.

Liz Zanis

Liz Zanis is a collections specialist in the Department of Drawings and Prints.