Reminiscences of a Bookbinder

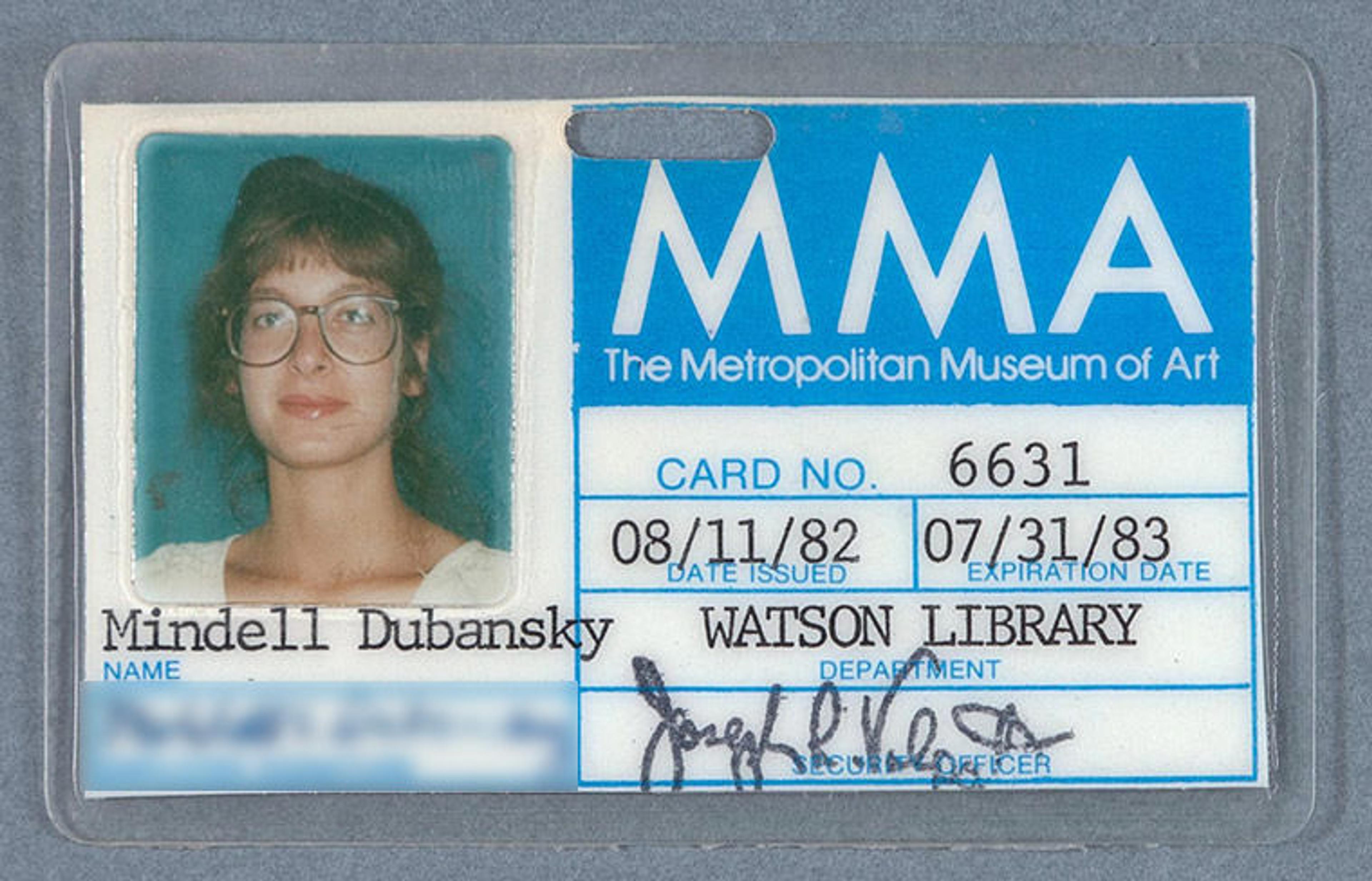

My first Metropolitan Museum of Art identification badge, dated August 11, 1982.

In celebration of the 150th anniversary of The Met and its library, Watson Library staff are writing In Circulation posts relating to the history of our library. Last August, I celebrated my 37th anniversary at The Met, and it has caused me to reflect on my experiences, accomplishments, and future goals as head of the library's Sherman Fairchild Center for Book Conservation. This post is more a series of recollections rather than a formal history.

I arrived at Watson Library for a job interview in late summer 1982. I was twenty-eight years old and this was my first formal interview, although I had previously worked as a hand bookbinder at the Center for Book Arts in New York City. I was freshly back from a year-long course in fine bookbinding and restoration at the Camberwell School of Arts and Craft in London. My interviewer was Chief Librarian William Walker, and the position title was Restorer. This position was the lone position in the library's bindery. The person hired would replace Nancy Russell, who had been here for seventeen years. Amazingly, I was hired the very next day and started shortly after.

My predecessor, Nancy Russell, demonstrating book repair in the 1970s.

At the time of my arrival, there were twenty or so departmental and independent libraries scattered throughout the Museum. Watson Library was, and still is, the main research library, and the bindery served its needs and provided some services for departmental libraries. The library additionally employed an independent commercial library bindery, Ocker and Trapp Library Bindery, which bound most of the soft-bound books and re-cased worn books from the (non-rare) general collections. The mandate I received from technical services staff upon arrival was to perform the established tasks required to protect and label fragile books, and to modify pamphlets and thin soft-bound books so that they could stand erectly on the shelves. While many of these processes added protection and strength to the books, others were somewhat destructive, and I modified them as much as possible.

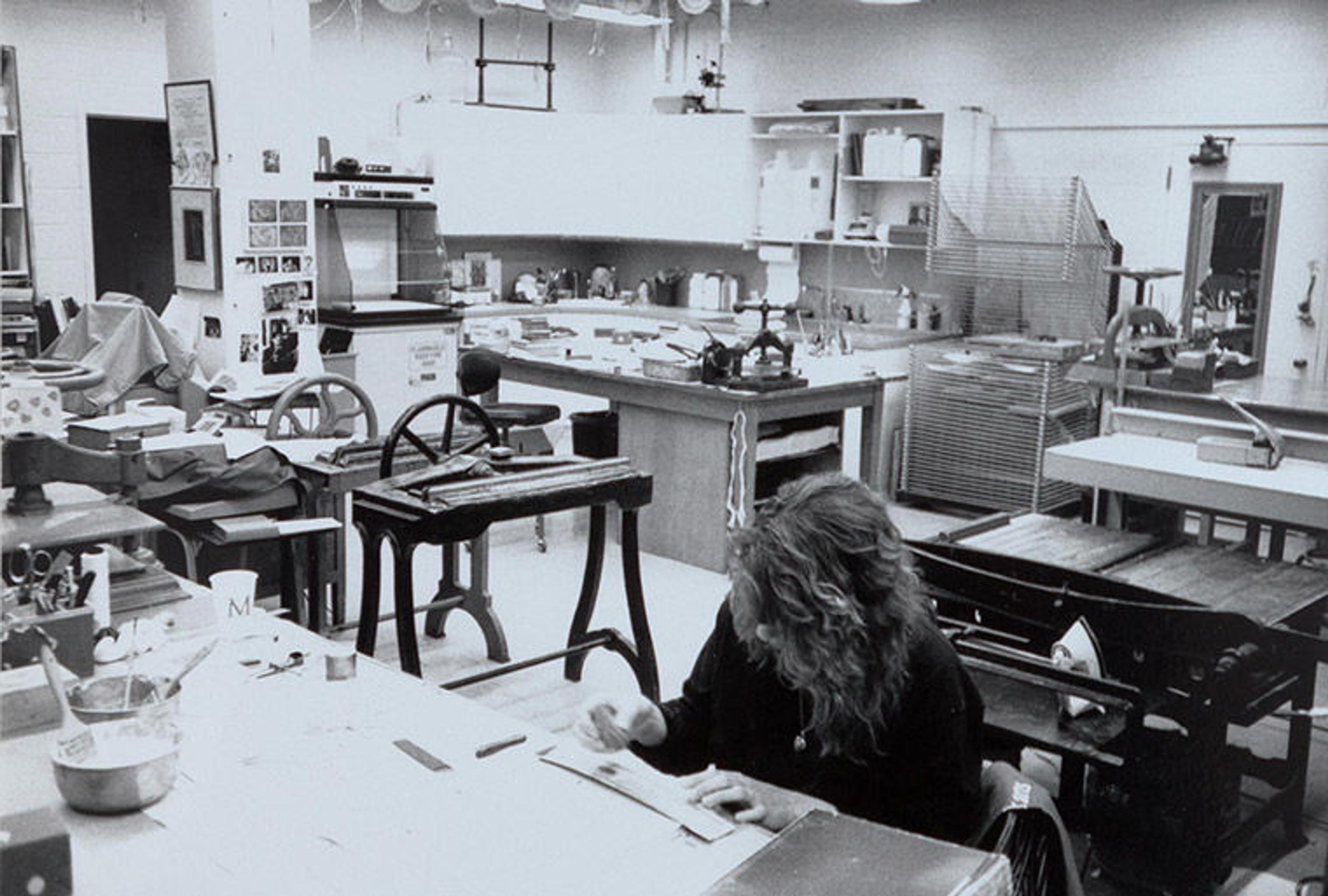

Early days working in the bindery, which was at the time only a part of the room we now fully occupy.

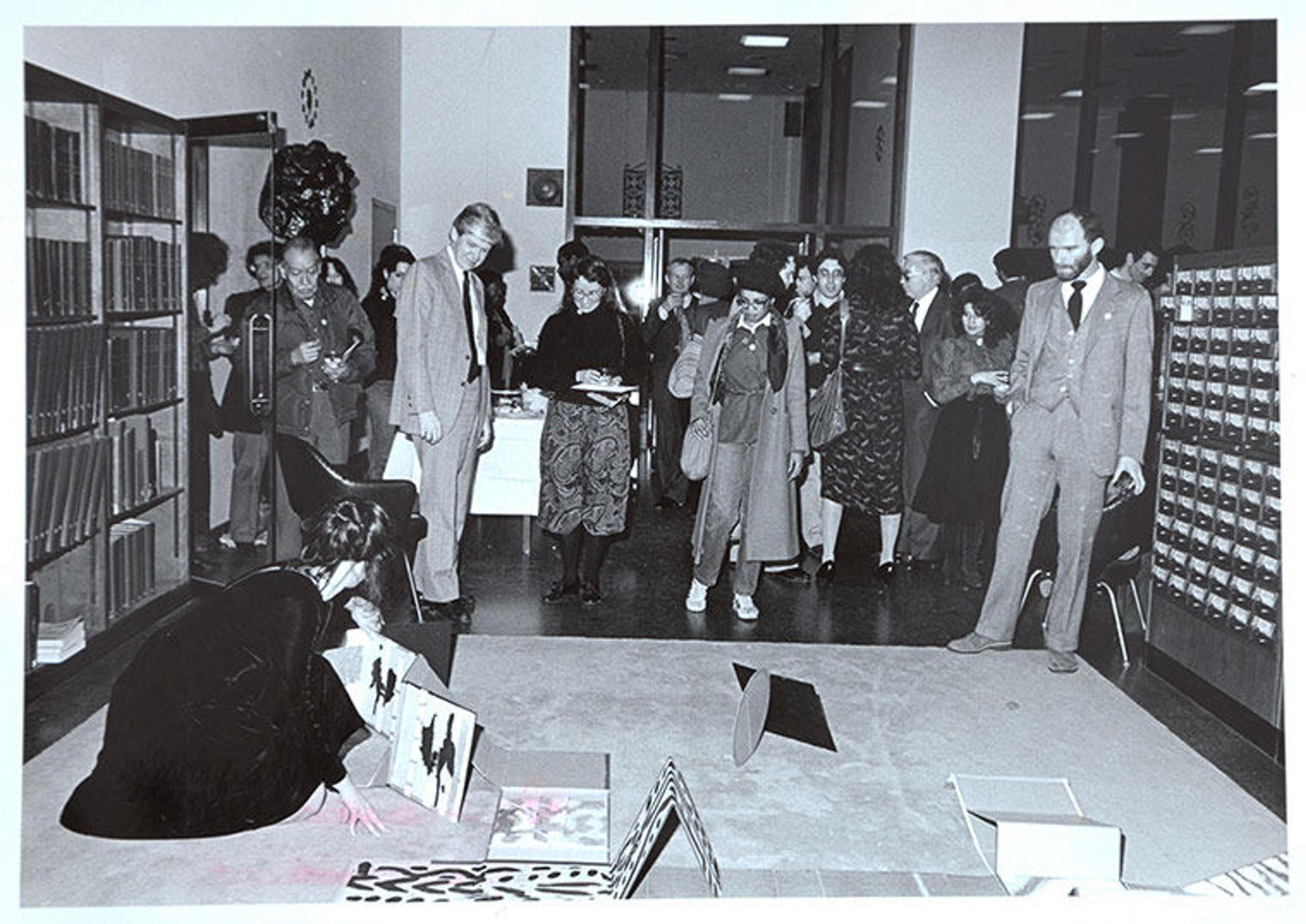

After settling in, I quickly set out to attract skilled volunteers and staff, develop the facility, and launch a book-arts exhibition program which thrived between the years 1982 and 1990. During that time, the library hosted over thirty exhibitions, collaborating with numerous book arts organizations including the Guild of Book Workers, Printed Matter Inc., The Center for Book Arts, Dieu Donné Press and Paper, and The University of Iowa Center for the Book.

A demonstration of Susan Share's expandable book box at the opening of my first book arts exhibition, Books Alive (January 12-February 10. 1983), which I co-curated with Share. Chief Librarian, William Walker, is the tall gentleman, front left.

Things were changing rapidly in the field of library preservation and book conservation in the early 1980s. Concerned librarians and preservationists had identified the problems associated with brittle paper and the loss of our cultural heritage, and advocated for reform. In 1981, a transformation occurred in the library world, and it happened in New York. Paul Banks, a book conservator previously working at the Newberry Library in Chicago, established the first degree-granting program in library preservation and conservation at the Columbia University School of Library Science. I was able to attend this program with the library's support from 1986 to 1988, graduating with an MS in Library Service and a Certificate in Library Preservation Administration. The knowledge and confidence I gained through completing these programs allowed me to reshape the direction of the bindery towards preservation and offer our services equitably to all Museum libraries and rare book collections. Specifically, it was during this period when I began writing and receiving grants to conserve the rarest and most valuable books in the Museum's collections. These awards have mainly been used to conserve and rehouse rare books in the Department of Photographs and the Department of Drawings and Prints. Funds for these treatment projects have consistently come over the years from the Conservation/Preservation Discretionary Grant Program of the New York State Library. Sophia Kramer has been the conservator on this project for the past twelve years (read more about these projects here).

Some improvements were made to the original bindery by the late 1980s. The full room was reclaimed and bookshelves were replaced by a new wet area. Still, this was a far cry from the beautiful Sherman Fairchild Center for Book Conservation that was to be. Paula Hacker Schrynemakers is the conservator working in this photo.

In 2009, two monumental occurrences spurred great changes in the library and for book conservation staff. These were the consolidation or realignment of the Museum's libraries into a cohesive library system under the direction of the chief librarian, Ken Soehner, and the renovation and expansion of the book conservation facility, which was formally completed and renamed in 2011 as the Sherman Fairchild Center for Book Conservation. The library realignment created a cohesive, inclusive Museum library system. The renovation was a metamorphosis. What was once an underground cinderblock workroom became a state-of-the-art book conservation facility, which is a pleasure to work in to this day.

Newly renovated lab, completed in 2011. The perspective is similar to that of the photo above. In addition to the fully renovated space, we gained a mezzanine, allowing us to separate conservation and administrative functions. Its unique mezzanine sculptural wall was designed by Beatrice Coron.

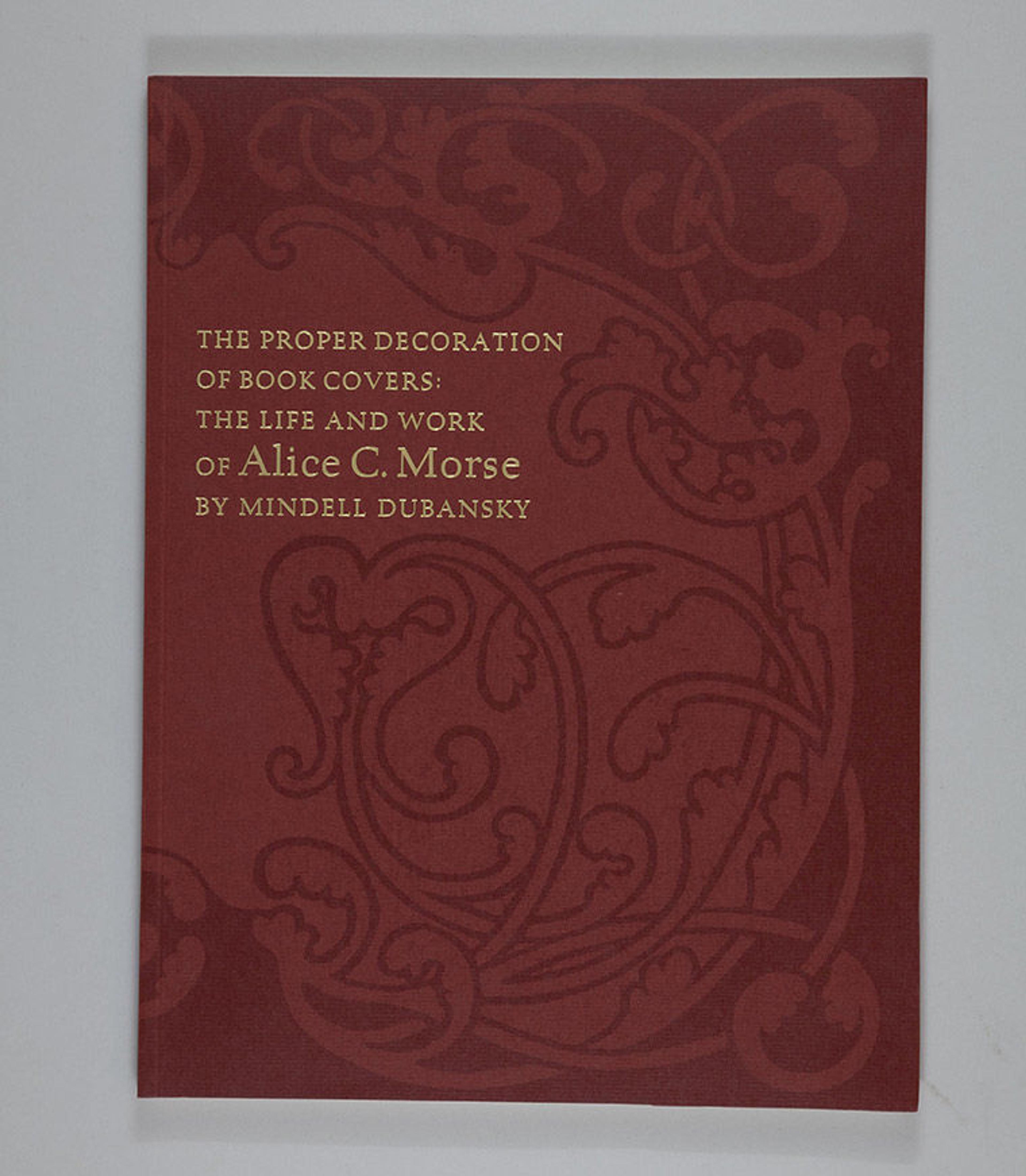

The history of the book and book arts have always been important to me, and I have considered their study and advancement to be an integral and important part of my position, Museum Librarian for Preservation. This research has been accompanied by collection building for the library. Subjects in which I have succeeded in making an impact are American publishers' bindings and the work of designer Alice C. Morse; and twentieth-century decorative paper arts, or the Paper Legacy Project. There will be an exhibition of the Paper Legacy collection at the Grolier Club in the fall of 2022.

Decorative paper artists Sage Reynolds and Iris Nevins visiting the lab and meeting each other for the first time. We are showing one of Iris Nevins's papers from her Paper Legacy collection.

Another subject in which I have studied is the history of book-shaped objects, but this is something I engage in for my own amusement and understanding of the world of books. I did however, write a blog post on the Museum's collection of book objects.

Alice C. Morse, designer, 1863-1961. My research on Morse led, over a fifteen year period, to the production of a study collection of books she designed and an exhibition at the Grolier Club that was accompanied by the illustrated catalog The Proper Decoration of Book Covers: The Life and Work of Alice C. Morse (New York: Grolier Club, 2008).

It would be difficult to mention and thank all of the staff, interns and volunteers who have contributed their skills over the years to the care and repair of the collection. One that must be mentioned is Alfred Launder, the Museum's first book bookbinder, who came to work in the Department of Prints in 1929 and wrote the manuscript A Textbook for Rebinding Rare Books, Based on a New Technical Principle, an early conservation manual based on his work at The Met.

Upon retiring, Launder trained a binder named Walter Moore, who can be identified by his signed bindings. Following that, there appears to have been a string of others, none as notable as Launder, and I have always added their names to collection surveys I have performed.

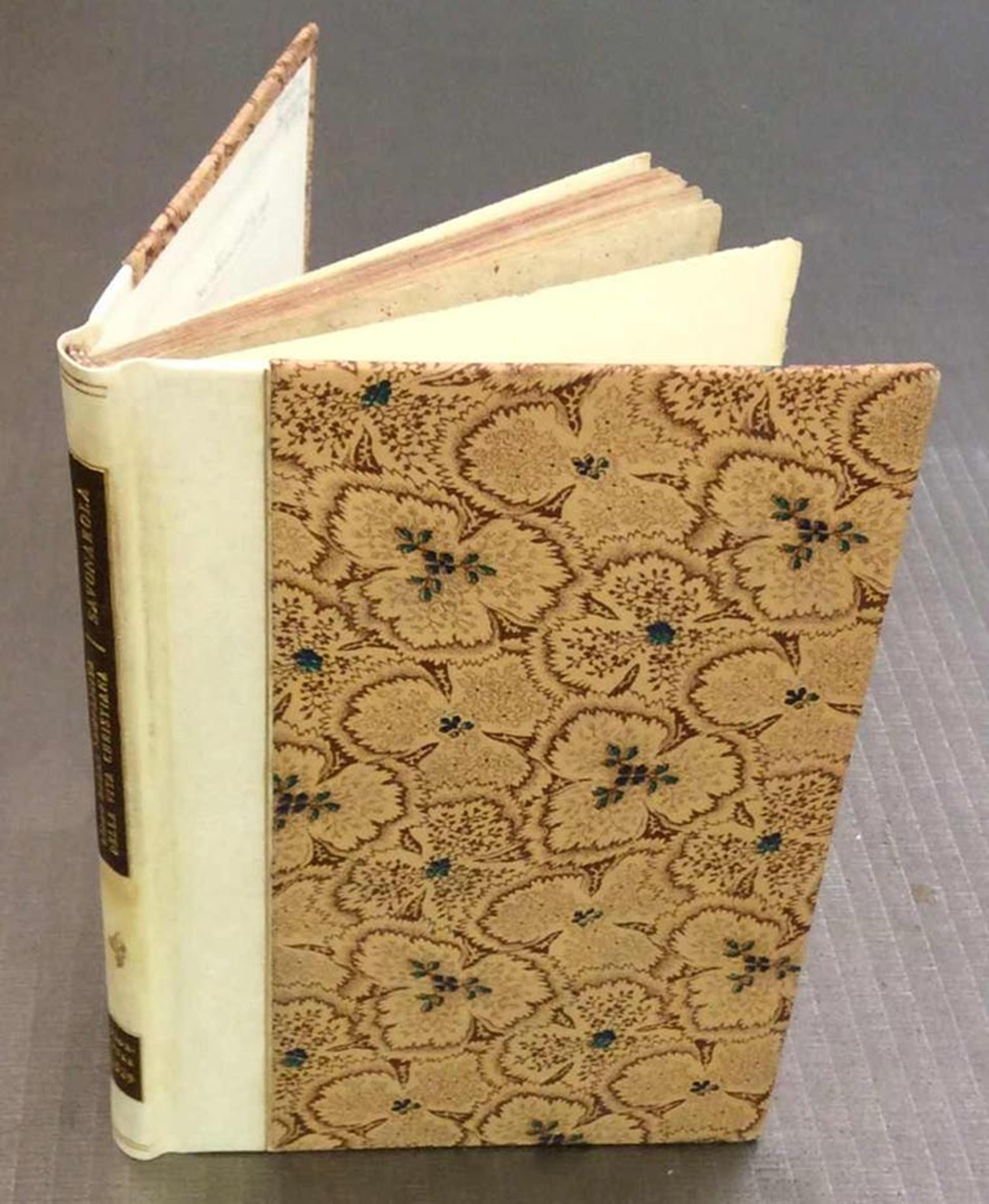

One of Alfred Launder's bindings for the Department of Drawings and Prints. This one has a vellum spine and a printed cotton fabric cover. Although the structure is hidden, the book is bound in the same technique that Launder describes in his manual. All of Launder's bindings, no matter how simple or functional, have hand-tooled embellishments, which harken back to his distinguished career as a finisher at Bradstreet's bindery.

As for the library, records are scarce. In the mid-1990s, prior to his retirement, I interviewed Patrick Coman about the evolution of book repair in the library and the names of my predecessors. Pat came to library as a library technician in 1957 (before it was the Thomas J. Watson Library) and retired in 1995. Notes from our discussion state that in 1957, the library was in a different location and the bindery was on the ground floor. In the mid-1950s, Pat was sent to the tower of Rockefeller Church to learn bookbinding for two evenings each week and he performed some binding for the library at that time. By 1962, Francis X. Kelley was the bookbinder and supervisor of the technicians. Kelley was not a trained bookbinder, however he made enclosures, assembled pamphlet bindings and did some repairs. Kelly was followed by Mr. Porkorny, a bookbinder who stayed only briefly (he was apparently laid off because of his unfortunate habit of stripping down to his undergarments) and was followed in 1963 or 1964 by Hans Beckmann, master binder, who remained in the Library for three years. Beckmann worked on books both onsite and at home; he was succeeded by Nancy Russell.

That brings us to my tenure and the numerous staff conservators and bookbinders who have made it possible to conserve the over four thousand books that flow through book conservation each year and participated in the success of our numerous projects and programs. Staff include Susan Share, Henry Pelham Burn, Paula Hacker Schrynemakers, Jayne Hillam, Sisi Myint, Sarah Dillon, Judith Hanson, Franziska Richter, Jae Carey, Talitha Wachtelborn, Nora Lockshin, Mirah von Wicht, Georgia Southworth, Claire Manias, Jenny Davis, and of course our current staff Andrijana Sajic, Yukari Hayashida, Sophia Kramer, and Shayla Nastasi. If I've forgotten anyone, I apologize. I'd need a book to mention all of our priceless volunteers and interns, but if you are reading this, know that you and your work have been and are appreciated and valued.

I have had a long and rewarding career at The Met, for which I am extremely grateful and honored. The collection is remarkable. It surprises and informs me every day. As a child I knew I wanted to work in a museum or library, but I had no idea it would have been possible to do both. It's been a true blessing, I still have to pinch myself even after all these years.

The current staff of the Sherman Fairchild Center for Book Conservation, Thomas J. Watson Library. From left to right: Sophia Kramer, Yukari Hayashida, Shayla Nastasi, Mindell Dubansky and Andrijana Sajic.

For more in this series on the history of The Met's libraries, click here.

Mindell Dubansky

Mindell Dubansky is the Museum librarian for preservation in the Thomas J. Watson Library.