Valentine's Day and the Romance of Cobwebs

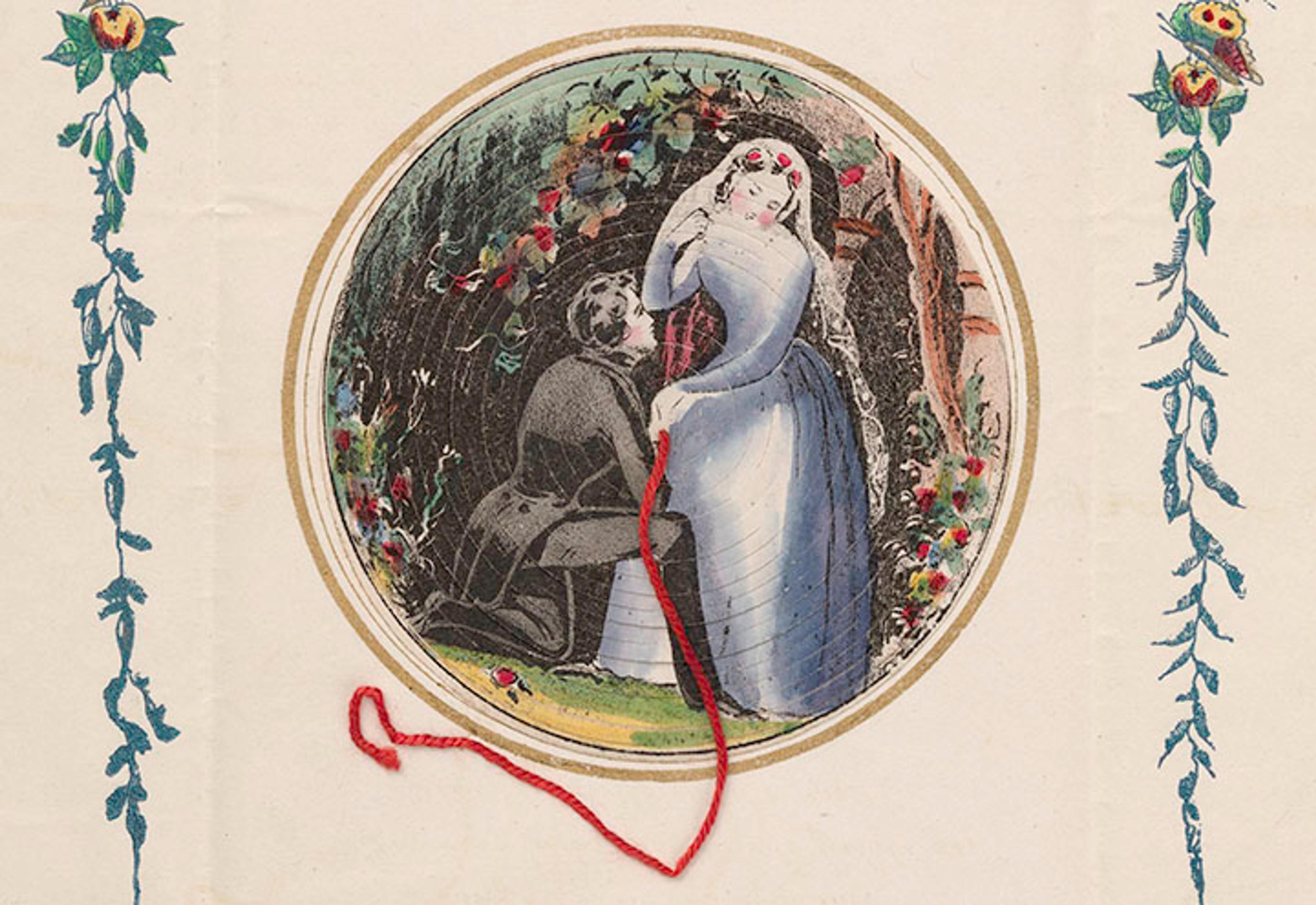

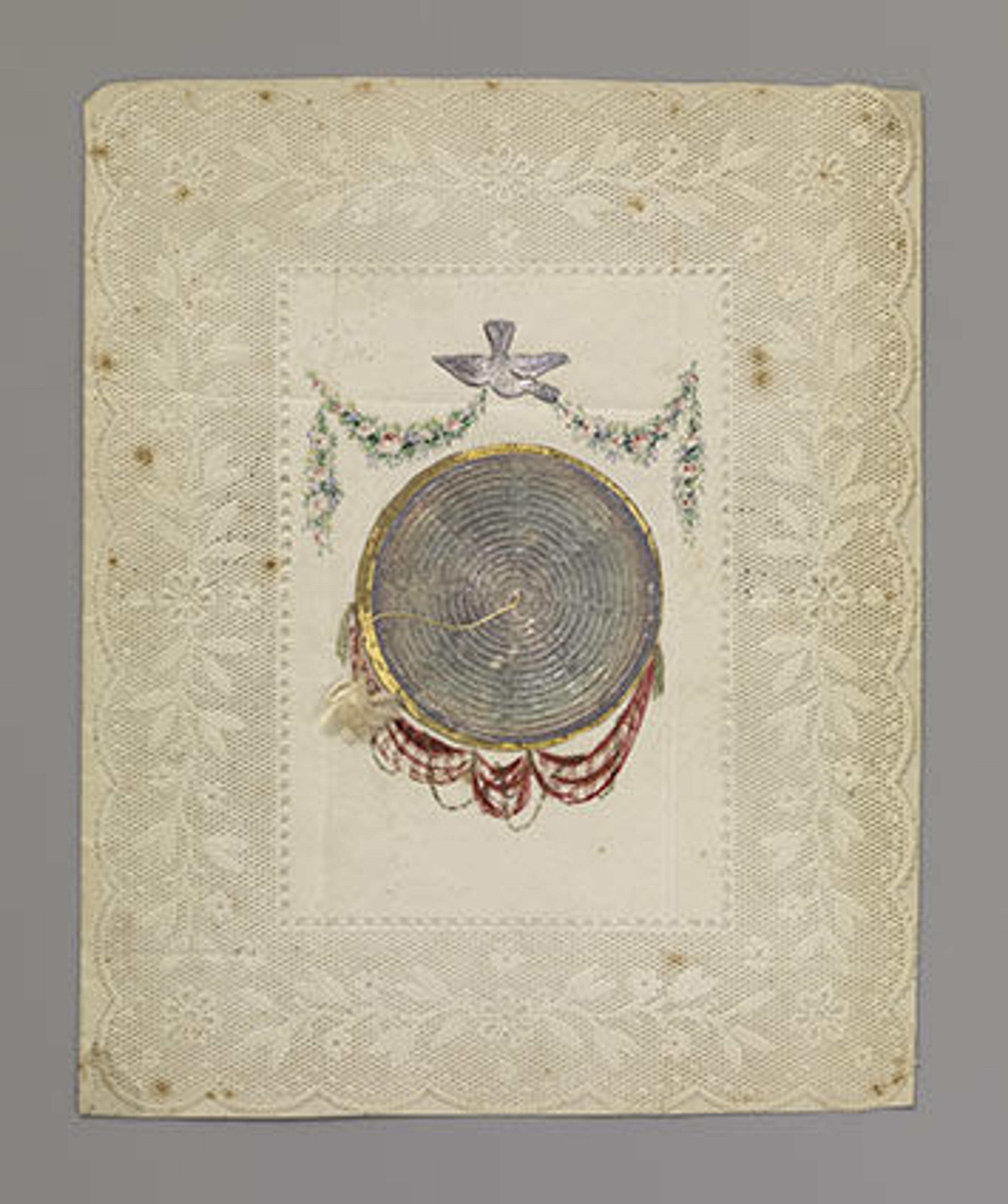

Anonymous (American, 19th century). Cobweb valentine, 1847. Wood engraving, letterpress, and watercolor, Sheet: 10 1/16 x 8 11/16 in. (25.5 x 22 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Mrs. Richard Riddell, 1981 (1981.1136.555)

«Among the many works on paper in The Met's Department of Drawings and Prints is a large collection of historic valentines from Europe and the United States. In paper form, these tokens of love are known from the 17th century onwards, and were either handmade or, from the mid-18th century onwards, produced as commercial products by printmakers and manufacturers of paper goods.»

As a result of advances in printing and paper-making techniques, as well as the development of an efficient and inexpensive means of postal delivery, the custom of sending greeting cards and gifts on Saint Valentine's Day reached its pinnacle around the mid-19th century. The popular holiday was embraced and celebrated across all strata of society with parties, balls, and the quintessential elaborate paper greetings that became a veritable hallmark of British and American Victorian life. Whether sentimental or satirical, simple homemade missives or fancy machine-made confections, everyone hoped to receive a valentine from a beloved on February 14. Chronicling the most intimate communication between private individuals, the valentines that have been preserved give us a unique look into the sentiments, hopes, and dreams of generations of lovers, and the means through which they chose to express them.

As a passionate collector for more than 40 years, I have been given the unique opportunity to explore and catalog part of the rich array of these treasures within the Museum's collection. Donated and collected over several decades, the collection contains many rarities, and it is my pleasure to share some of the details and intricacies of these enchanted expressions of love. So in honor of Valentine's Day, I present a few very special reflections of 19th-century romance known as so-called cobwebs.

Cobwebs—also known as beehives, flower cages, or birdcages—are a rare example of a mechanical or movable valentine consisting of a minimum of two layers of paper. First, a web or cage would be cut from a piece of paper by making a pattern of concentric circles, leaving attachment points at regular intervals. In the center of the spiral, a delicate thread would be attached and its outer edges would be pasted directly on top of a second sheet on which an image or message would be written, painted, or printed.

As a cover, the cobweb formed the perfect sanctuary to enclose a private message that could only be revealed when the recipient of the card carefully pulled up the thread, causing the concentric circles of the web to rise and magically expose its hidden compartment. The concept of secrecy and the element of surprise frequently recurs in valentines, as they speak to the intimacy that has always been a part of the language of love and is one of the reasons why the cobwebs were so popular.

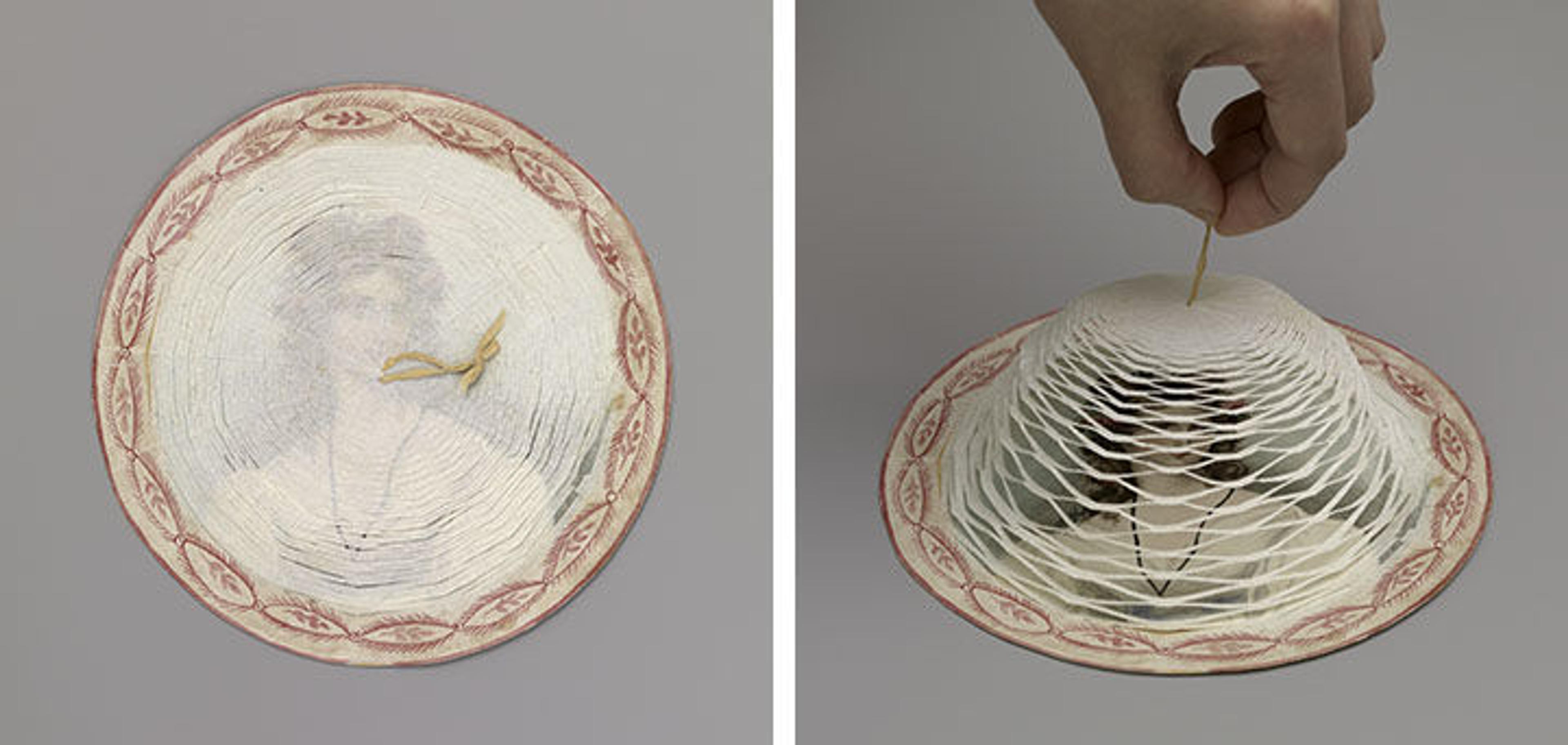

Anonymous (American or British, 19th century). Cobweb valentine, 1830–40. Watercolor, cut tissue on board, Diameter: 6 1/2 in. (16.5 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Mrs. Richard Riddell, 1981 (1981.1136.510)

Cobwebs could be made by hand or bought as a machine-made product, both with various levels of intricacy. For the more modest handmade version, let's first look at a simple circle of cardboard dated around 1830–40 (above). The web itself is cut out of a thin white tissue paper, and is edged with a pink watercolor border. A tiny yellow ribbon at the center allows you to lift up the carefully cut web, revealing a glorious portrait of a beautiful woman. Her long, dark ringlets are caught at the sides with roses, and she wears a golden locket suspended from a black cord over her bodice. Through the protection of the tissue web, the image has retained its vivacity over the 200 years since it was produced.

One of the most elegant and complex cobwebs in The Met collection uses symbols to add to the hidden message of the valentine. The attributes and symbolism of flowers, in particular, could speak to an array of secret messages or desires, which is why they recur so often in the design of many valentines. These were often painted or printed, although fabric or dried flowers were sometimes used as well.

Left: Anonymous (British, 19th century). Cobweb valentine with morning glory, 1840. Watercolor, pen and brown ink on cameo-embossed paper, Sheet: 7 7/8 x 9 3/4 in. (20 x 24.7 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Mrs. Richard Riddell, 1981 (1981.1136.540)

This card's crisp and clean interior may look brand new, but the soiled exterior reflects its travails as one of the more than 60,000 that are estimated to have been sent at that time. It was folded, sealed with wax, and postmarked in 1840, when it made its way to its addressee, a Miss Eliot, at Shooter's Hill in Kent, whom, judging from the complexity and the associate cost of this valentine, must have been very important to the sender!

At first sight, this valentine seems to present a simple but elegant offering with a composition of roses, forget-me-nots, and oak branches around a painted morning glory, or convolvulus, that give little hint of the surprises this card has in store. On second view, one notices the unusual twisted base of the central flower. When very gently untwisted, it opens up to reveal a round compartment decorated with a beautiful watercolor bouquet that, in turn, contains a cobweb device: delicately lifting the thread reveals the interior image of a dove.

From the highly detailed embossed cherubs and oak leaves in the paper—made by the London manufacturer Dobbs and embossed DOBBS PATENT—to the hand-painted flowers, this valentine is a beautiful example of layered eloquence. In the Language of Flowers the morning glory represents love and affection, but also unrequited love; the rose stands for love; the forget-me-not symbolizes true love and memories; and the oak and acorn signify strength, potential, and patience. Collectively these flowers communicate a message without the need for the written word, which is all the more important since the card appears to have been sent without a handwritten message to accompany the imagery. Anonymity was part of the tradition of valentines and since many women were graced with numerous admirers, guessing the sender was an integral part of the fun.

A special form of the cobweb valentine is the so-called double cobweb. Using a variety of paper engineering feats, double cobwebs could be arranged on the page side by side, one on top of another, or even emanating from attachments at both top and bottom (recto and verso) of the pages. The double cobwebs in The Met collection are rarities, and were donated by Mrs. Richard Ridell. Her collection reflects the inquisitive passion she had for historic ephemera, and greatly enriches the depth of our knowledge about the valentine from its English and Austrian origins.

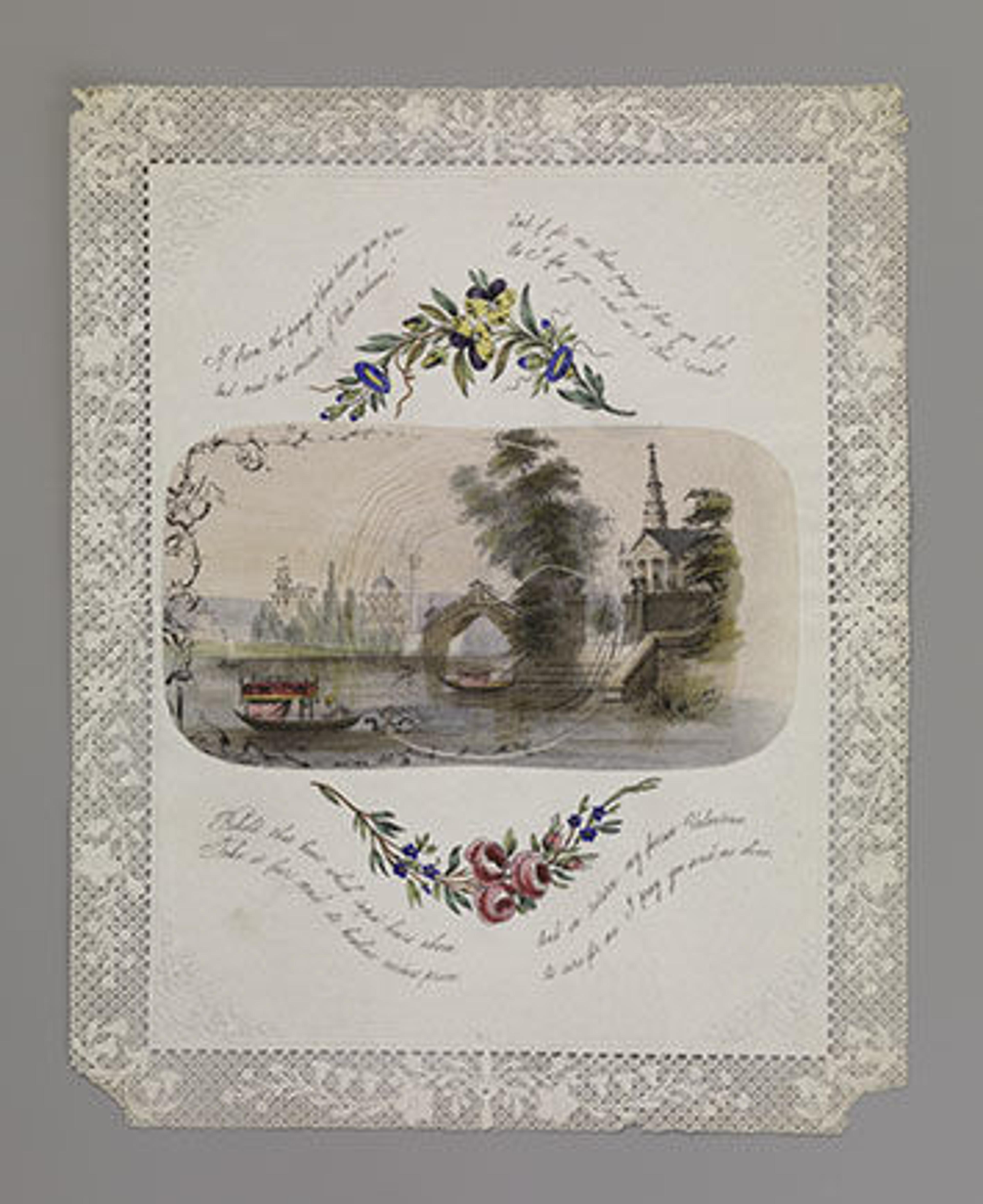

An exquisite example of a double cobweb is this single-sheet valentine with a picturesque landscape scene in hand-colored lithography, containing a Venetian-style bridge, a romantic canopied gondola, and a stairway leading directly from the water to the church on the right. Drawings of pansies and roses further decorate the page and add to its romantic visual messages. The center has been hand-cut into a double cobweb, positioned one within the other.

Right: Anonymous (British, 19th century). Double cobweb valentine with Venetian scene, 1830–50. Lithograph, watercolor on openwork cameo-embossed paper, Sheet: 9 3/8 x 7 1/2 in. (23.8 x 19 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Mrs. Richard Riddell, 1981 (1981.1136.534)

The cut cobweb lifts open to reveal an image of Cupid presenting a heart—"Love's Medicine," as the inscription explains—to a woman reclining inside the gondola. A second, smaller cobweb is located inside the larger one, and is exposed only upon lifting the first. A man is depicted helping a woman disembark from a boat as they are guided by Cupid to the Altar of Love. A cherub soars above carrying the flaming torch of Hymen, the god of marriage.

Left: Anonymous (British, 19th century). Metallic double cobweb valentine, 1845. Lithograph, watercolor, metallic paper on embossed paper, Sheet: 9 1/16 x 7 5/16 in. (23 x 18.5 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Mrs. Richard Riddell, 1981 (1981.1136.547)

Tarnished and spotted by age, this is definitely a hidden treasure and a spectacular game of love. The silver disc, once shiny, was machine-cut into a cobweb. The surprise occurs when the tasseled thread attached to the top center is gently pulled. Two images appear, one beneath the other. The silver circle lifts to reveal its cobweb, and that, in turn, reveals a golden disc, from which is suspended yet another cobweb. The top image is a hand-colored lithograph of a woman with butterfly wings holding a bouquet. The second image shows a man standing behind a seated woman; he appears to be looking at a locket in his right hand. Double cobwebs are a rarity, and this mechanism is incredibly unique.

It is easy to understand why today's collectors covet these cobweb valentines. Far from being ephemeral trifles, these were cherished mementos, and to many collectors like myself, their tactile quality is a very personal connection to history, individuals, and the sentimental past. It is wonderful to see that The Met recognizes the value of this material, not only as popular culture, but also as an art form that reflects an important aspect of our social history.

Nancy Rosin

Nancy Rosin is a volunteer cataloger in the Department of Drawings and Prints.