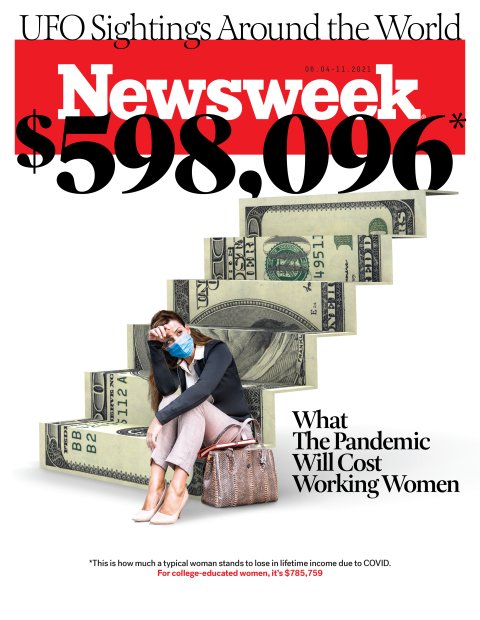

Fifteen months into the COVID-19 pandemic, the statistics that reflect its toll on women's employment continue to astonish. Women's participation in the labor force has dropped to levels last seen in the 1980s. A May 2021 analysis from the National Women's Law Center identified a net loss of 4.5 million jobs held by women since February 2020; nearly 2 million women have left the labor force altogether. And those sobering big-picture numbers obscure the outsized impact on women of color: The employment rate for Black and Hispanic women has taken a bigger hit than that of any other demographic group.

Early signs of the post-COVID recovery suggest the negative effect on women won't disappear any time soon. Research by McKinsey suggests the employment recovery rate for women will lag men's by a year and a half.

Women who've hung onto their jobs aren't faring well, either: Studies show that those with children have reduced their work hours exponentially more than their male partners, and are worried about how their performance is being judged. Meanwhile, regardless of parental status, women report being ignored or talked over in virtual meetings at higher rates than men, according to a Catalyst survey—an indication of the ways that remote work can increase subtle discrimination.

If all we do is try to get back to the pre-pandemic playing field, we'll have missed an enormous opportunity to treat the true causes of these dramatic disparities.

It's crucial that policymakers and researchers dig into these outcomes, analyze their impacts on the economy, and look for ways to accelerate an equitable recovery. But if all we do is try to get back to the pre-pandemic playing field, we'll have missed an enormous opportunity to treat the true causes of these dramatic disparities. The uneven effects of the pandemic are, ultimately, symptoms of deeper problems in the workplace that were present long before COVID-19—and will only calcify if organizations don't tackle them head on.

The truth is, the pandemic and the financial hits that resulted have merely revealed the extent to which our workplaces still don't work for women. As bleak as this realization may be, it points us toward a brighter future: If companies do the work now to cure the underlying disease, they can emerge stronger than they were before the pandemic roiled the world.

The disproportionate caregiving burden shouldered by women is, of course, a major factor in the past year of job losses and gender inequality overall, as is the concentration of women of color in hard-hit sectors and in industries with few job protections. But these phenomena do not fully account for the ways women continue to be marginalized and stymied at work, leaving them stretched thin, stressed out and inadequately rewarded for their contributions. Women were already burned out before the pandemic hit. Although many organizations have the best intentions when it comes to hiring, advancing and retaining women, the reality is they too often foster environments that leave female employees feeling diminished, disengaged and pessimistic about their prospects.

In a 2018 survey of MBA graduates that we conducted with colleagues at Harvard Business School, the proportion of women who reported they felt burned out from work "often" or "very often" was nearly double that of men, as it was for the proportion who said that experiences at work had negatively affected their mental health. Women of color reported the highest rate of burnout: close to 30 percent vs. just 12 percent of white men. The same pattern—women of color faring worst, white men best—held for the workplace's toll on physical health.

It's no surprise, then, that more women told us they were "very" or "extremely" likely to leave or try to leave their employers within a year. Again, the proportion was highest for women of color, with a fifth reporting that they planned to leave, compared to 13 percent of white men.

We can't know all the reasons work had deleterious effects on the stress and health of the women we surveyed, but other research we've conducted offers some clues. For our book Glass Half Broken: Shattering the Barriers That Still Hold Women Back at Work, we collected quantitative and qualitative data from hundreds of women in senior-level positions across a multitude of industries, from around the world. These executives, who had witnessed most of their female peers drop from the leadership pipeline, agreed: Women, they told us, are still not being treated fairly when it comes to all the basic processes an employee goes through.

Upwards of two-third of the female leaders we surveyed said that women were at least somewhat disadvantaged when it comes to applicant recruitment, hiring, integration, training and development, performance evaluation, and promotion and compensation. That last category elicited the strongest response, with over 70 percent telling us that women faced "a great deal" of unfair treatment regarding title and pay. It's surely no coincidence that women feel demoralized and frustrated in workplaces where they feel they're not getting a fair shake.

All of our data were collected prior to the pandemic, revealing that the inequities thrown into relief today were long entrenched. Last spring, we started hearing directly from women, just weeks into the new work-from-home reality. It soon became clear that employers were sharply divided in their approach: Companies were either paying careful attention to making the virtual workplace equitable or had completely forgotten to consider that workers might be navigating a range of challenges.

Many women who had thought they were well-regarded and valued at work found themselves overlooked in virtual meetings or left out of key conversations. Women with kids at home also felt the "motherhood penalty"—a well-documented phenomenon whereby mothers are viewed as less invested in their work than men and women without children—intensify as child-related disruptions exacted a reputational cost, even as they watched male peers get commended when they fielded similar parenting interruptions.

The status quo simply isn't good enough—not for women and not for companies that want to fully leverage their talent either.

The status quo simply isn't good enough—not for women and not for companies that want to fully leverage their talent either.

The solution is straightforward, though it will take real commitment to implement. Organizations must move away from ad hoc efforts to improve gender equity—a mentoring program here, an outreach to female undergraduates there—and dig into deeper change in the ways they operate. The managerial processes in which our sample of senior women saw persistent bias can be improved, with an evidence-based approach and willingness on the part of all managers to follow through. Social science has given us diagnostic frameworks for identifying the moments where gender bias skews our systems.

Take, for instance, professional development. An employee can't advance if she can't grow her skills and build a track record of accomplishments. Yet women often miss out on such opportunities, compared to male colleagues of comparable talent and aspiration. As a result, their career trajectories start to lag those of male peers, which in turn leads to an overrepresentation of women at lower levels—a key contributing factor to the gender pay gap.

It's common for managers to think they are supporting women by "protecting" them from challenges—a particularly tough client, an overseas assignment, a promotion that requires a cross-country move. This misguided impulse results in women systematically having less access to exactly the sorts of projects that will help them advance and reducing their control over their own career path. To move toward equity, managers must apply a more critical lens to their decisions about how to distribute stretch assignments, reflecting on their assumptions and looking for objective ways to assess who is best suited for a given opportunity.

The need for a systemic approach to gender equity in all aspects of management cannot be overstated, and it is central to all of the recommendations in our book. The systems and the leaders who run them, from frontline managers to CEOs, hold the cure for persistent gender inequality at work. Every step of the way, as early as writing a job description, companies must put their processes through a review to look for signs that women are put at a disadvantage.

When systems improve, and not before, women's experiences at work will change. As long as companies address only the symptoms of the underlying disease of structural inequality—say, focusing on turnover or disengagement—they'll see only marginal improvement. It's by repairing the broken structures that make women feel burned out, undervalued, unrecognized and ready to quit that organizations will come back from the pandemic stronger than before.

Colleen Ammerman is director of the Harvard Business School Gender Initiative. Boris Groysberg is a professor of business administration at Harvard Business School and a faculty affiliate at the Gender Initiative. They are coauthors of Glass Half-Broken: Shattering the Barriers that Still Hold Women Back at Work.