Another Extremist Law That Americans Have to Live With

An anti-abortion measure in Texas will change the practice of medicine. Pregnant patients will suffer.

Once again, politicians and judges are limiting abortion without any understanding of what pregnancy can, and often does, ask of the human body. To conservative legislators in Texas, a new law banning abortion after about six weeks of gestation is a ploy to subvert Roe v. Wade. But to doctors like me, the measure reveals how thoughtless its designers are and how willing they are to let pregnant patients suffer and die.

I’m an obstetrician who specializes in high-risk cases. Last month, I saw a woman whose water broke 19 weeks into a long-desired pregnancy. This patient, who had conceived after a previous miscarriage, was eager to have a child. When she came to the hospital, my colleagues and I told her the truth: Without an intact amniotic sac, she and her fetus were extraordinarily vulnerable to bacteria from the outside world. She might stay pregnant for the time being. But her chances of getting to 23 weeks—the point at which a baby might be able to survive outside her body, albeit with extensive, lifelong medical problems—were almost zero. While waiting to deliver, she faced a high probability of infection in her uterus, despite the antibiotics that we would give her. She was very likely to develop a serious infection, even sepsis, which could require a hysterectomy or, though unlikely, lead to death.

We told her that she could watch and wait, despite the risks. Medical standards also dictated that my patient be offered a termination of pregnancy right away, before she could become sick. We outlined ways to terminate her pregnancy: a procedure to evacuate her uterus in the operating room or an induction of labor with the understanding that the newborn would not survive.

This situation comes up at my hospital at least a few times a month, every month. Working with high-risk patients means I need to be able to discuss, recommend, and perform abortions somewhat regularly. This is not because I want to kill babies or end desired pregnancies. It is because, in many cases, I am walking patients and their families through a nightmare. Sometimes, abortion turns out to be the least terrible of all the progressively terrible options they face.

My patient last month thought about her choices for 12 hours and then asked us to induce labor—an option that would keep her safe but allow her to hold her baby’s body. We administered the same medications used for all medical abortions. A few hours later, she delivered a baby quietly, weeping the whole time. She held her baby for the four minutes of its life in this world, and our team wept with her.

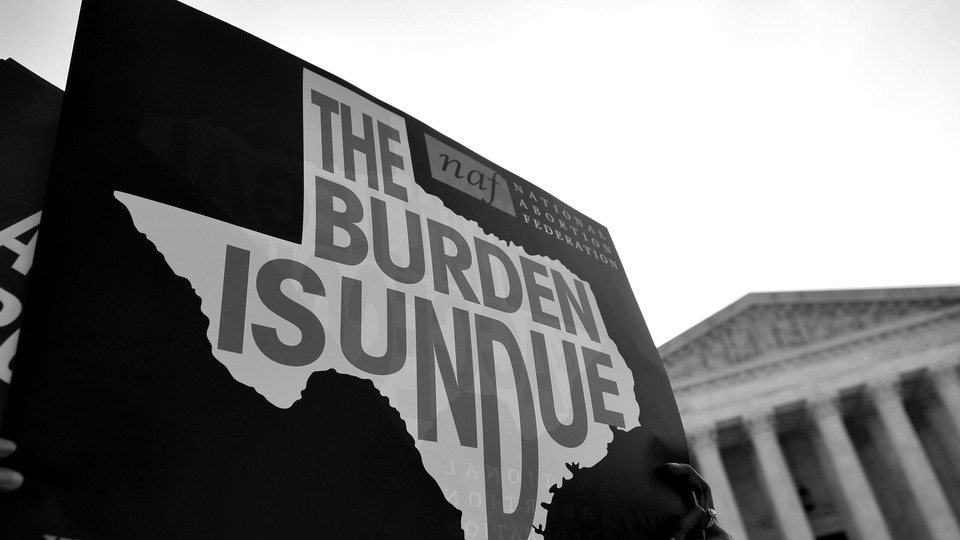

I practice in New York, where I can offer patients the choices they need. But in Texas, a new law, Senate Bill 8, prohibits abortion after a fetal heartbeat is detected—generally about six weeks into a pregnancy. People who perform or even assist in an abortion after that point can be sued by any person for a minimum of $10,000. Under this law, a medical team would have been taking an enormous risk by offering my patient any option besides waiting. But by the time a patient develops a fever and chills, and their heart rate goes up and their blood pressure goes down, they might be too sick for doctors to help anymore. In the tragic case of Savita Halappanavar in Ireland in 2012, a medical team refused to terminate a pregnancy as long as a fetal heartbeat was detectable. The shock of Halappanavar’s death led to far-reaching reform of Irish laws.

Although S.B. 8 makes an exception when the health of a pregnant patient is at stake, doctors who perform an abortion in such a case would be gambling that they’d be safe from the punitive intent of the law. The threat of litigation inevitably changes the practice of medicine. To feel safe from legal jeopardy in my patient’s case, we might have waited until she’d become febrile or showed other signs of infection before concluding that her health was in jeopardy. That point might have come too late to save her uterus, or her.

If putting patients and doctors in that situation sounds cruel and stupid, that’s because it is.

Every week, I see examples of morally necessary pregnancy terminations that, under the Texas law, could put doctors in legal jeopardy. In one case, a 14-year-old with brain damage had been raped by a caregiver. In another, my diagnostic ultrasound 15 weeks into a patient’s pregnancy showed that her fetus had developed an empty space where a brain should be and would not survive more than a few hours past birth. In another case, a patient, whose heart had become weak during her previous pregnancy and had never fully recovered, sought an abortion so she could live to care for her toddler.

If I worked in Texas, anyone could sue me under the new law. But not just me. Anybody could also sue you, should you be the secretary who made the appointment; or the neighbor who watched other kids to make the appointment possible; or the Uber driver who took the patient to the clinic. The payout is at minimum $10,000 per defendant, with no upper limit.

In this way, the law creates a mercenary and adversarial relationship between a community and its medical providers. Reproductive health care depends entirely on trust. You must feel free to talk with doctors like me about postpartum depression, sexual dysfunction, abusive boyfriends, or the occasional cigarettes you still smoke when stressed. And doctors must be able to honestly discuss the options, including pregnancy termination, that could save your life. If your doctor has to worry that any conversation could lead to a patient, or their disgruntled partner or disapproving relative, filing a report in order to make $10,000, that doctor may not be able to keep practicing.

Who would provide complex pregnancy care in such a setting? About half of U.S. counties already lack an obstetrics-and-gynecology provider. I cannot imagine why a newly trained obstetrician would agree to work in Texas under the current law.

And yet when the law took effect, and when the Supreme Court declined to block it, I couldn’t feel any outrage, or surprise; all I have left is a familiar deadening sadness. The United States has been heading in this direction for years, or even decades, as small and large legal actions have chipped away at abortion access by requiring ultrasounds that serve no medical need, and inappropriate but legally mandated counseling, and waiting periods that exist purely to add another logistical barrier for people who have already made up their mind to end a pregancy. Eighty-seven percent of counties in the U.S. already do not have an abortion provider; many of the ones that do have a doctor flown in one day a week, at considerable personal risk. Getting an abortion in most of the United States is already generally the privilege of people who are wealthy or who live in the right jurisdiction, or both.

This is true despite the fact that most Americans think Roe v. Wade should not be overturned; a significant majority of Americans support some level of legal abortion. Texas has enacted just another poorly thought-out law—an extreme measure, like the ones banning pandemic-control precautions and promoting the proliferation of guns, that most Americans do not support but somehow find themselves living with. If allowed to stand, the Texas abortion law will be replicated in other states—further steps in constructing a world that endangers patients like mine, that most of us don’t want to live in, and that we certainly do not want to hand off to our children.