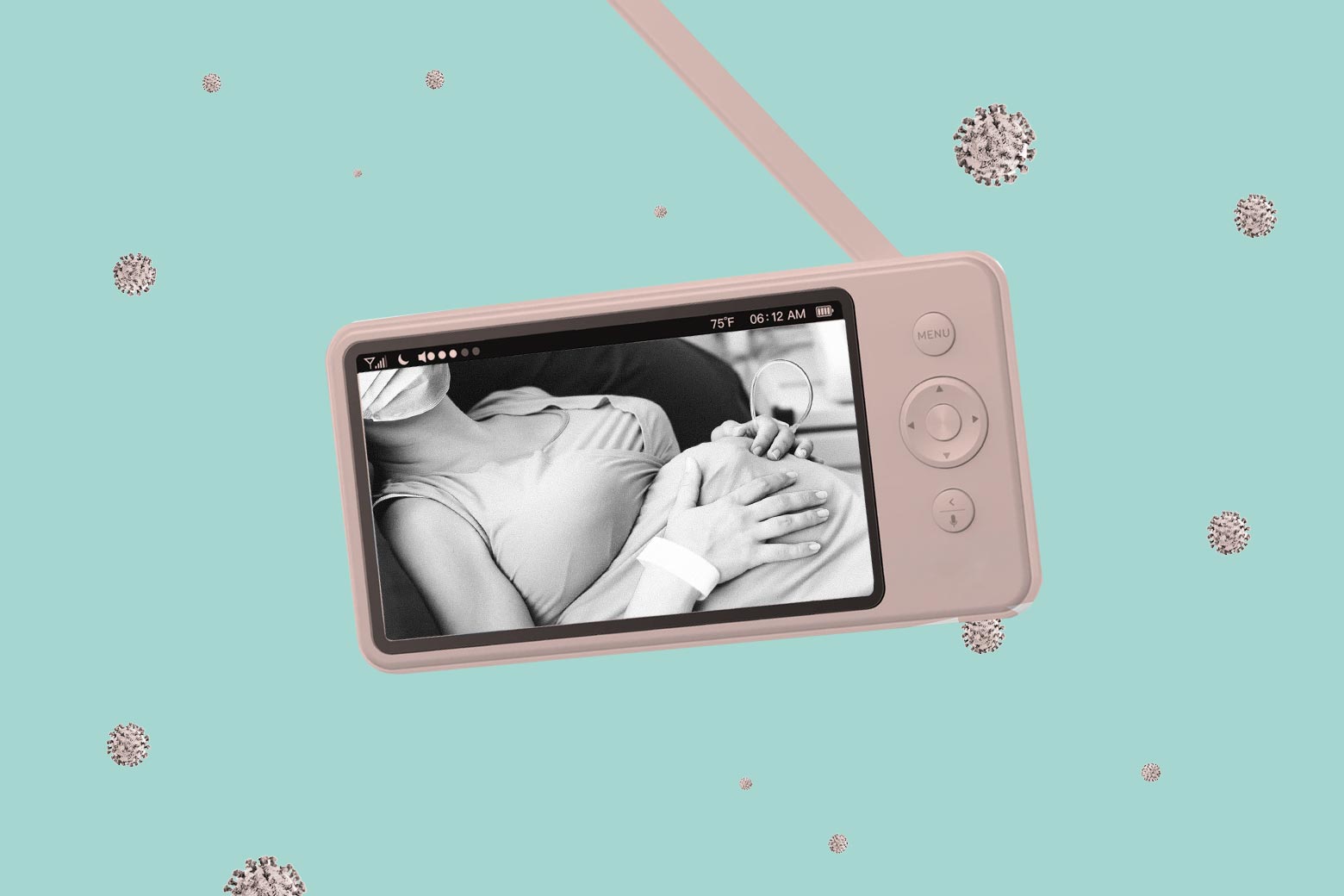

I want to give you an idea of what it feels like to do something important, dangerous, and entirely stupid—and then to have to do it all again. To do that, I would like you to consider the baby monitor: a 5-inch screen and a camera that can, from rooms away, watch an infant rest or fuss. For months, I have had a bag of baby monitors under the cramped desk in the tiny room that serves as my office at the hospital where I work as a high-risk obstetrician. They are not special baby monitors; they are the same ones you could buy on Amazon or at CVS. They’re stacked alongside a plastic bin full of clogs and a box of unused printer paper—the kind of things you can’t quite throw out, because you might need them.

You might think you know why a high-risk OB office has baby monitors—to monitor babies, of course!—but you’d be wrong. We monitor fetuses, not babies. Once the baby is out in the world, it goes to different doctors. We are not supposed to have baby monitors. We have baby monitors because of COVID-19.

Starting in late March, our hospital in New York was overwhelmed with COVID patients. The emergency department became full; and then, quickly, the ICU was full, and then the supplemental ICU was full; and then the annex to the supplemental ICU was full. They put COVID patients in a banquet hall. And yet, people kept arriving.

The pregnant women with COVID were admitted to our department. Young, generally healthy women, often in the second or third trimester would come in by ambulance, leaning forward, gulping desperately for air between sentences. Some had fevers, most had a cough; every single one was terrified. In those first few days and weeks, we didn’t have many COVID tests available, but it almost didn’t matter: The truth would appear in the lung X-ray, those opaque clouds floating around the image that said “COVID pneumonia.”

We put those patients on our high-risk pregnancy floor, isolated, but just down the hall from our patients with the usual pregnancy inpatient issues, like preterm labor, kidney infections, preeclampsia. Our COVID patients were not sick enough to get a spot at the overflowing ICU; additionally, we wanted to keep them within reach of pregnancy-specific care. They needed oxygen, sometimes a little, sometimes a lot, sometimes changing day by day or even hour by hour. Our patients’ index fingers were taped to a pulse oximeter, beeping and blinking along with their oxygenation percentages: 95, 89, 98, 99, 94, 99.

We needed to watch those blinking numbers constantly, but our unit isn’t an ICU. We didn’t have the equipment to watch that pulse oximeter from the nursing station down the hall. And every visit to check the oxygen status in person meant another set of precious PPE, at a time when we never knew if we would have enough, and another staff member exposed once more that day.

One of our brilliant trainees thought of baby monitors, a hack that hospitals across the country used this spring to keep tabs on patients. He ran to the drugstore across the street from the hospital and bought four of them right off the shelf. We placed the “baby” part of the monitor in the patient’s room, focused on her pulse oximeter. We set up the “parent” part at the nurses’ station. One of our doctors sat there with two, or four, or six baby monitors lined up on the desk. We watched the oxygen numbers go up and down, up and down, making sure that we were constantly vigilant.

If the number dropped below 95, we would put on our gloves and gowns and eye shields, and second mask, and second gloves, go in, and change something. Sometimes we would tweak the oxygen or have the patient lie in a different position. Sometimes we would upgrade her oxygen equipment from a small nose tube to an oxygen mask.

Sometimes she needed more help, and we would call critical care and discuss intubation. For a patient that sick, we would also start to talk about whether to have her deliver early. We would weigh the stress of delivery over the amount of lung volume it would return to her, since babies in utero press against the diaphragm; we would try to discuss with her the impossible mathematics of how premature her baby would be and what kind of complications that baby might experience. We would weigh that with her against continuing her pregnancy and the complexities of managing an intubated pregnant patient. (We would always wonder if the choice we ended up making was the right one.) But if her numbers went up with our changes, we would leave, remove our PPE, and keep watching those baby monitors until the next time.

The baby monitors allowed our high-risk pregnancy unit to become a makeshift critical care unit. We used the baby monitors for March, April, and May, as cases surged, and then finally began to fall, in New York. By June, sometimes there was only one active baby monitor on the nursing station desk. Weeks later, there were none. The lockdown had worked. No further pregnant patients with COVID pneumonia needed them

My colleagues packed up the baby monitors, along with our makeshift face shields and masks donated by the public. We no longer needed the inventive things we had come up with during our terrible spring. But we didn’t throw the baby monitors out or give them away. We stashed them upstairs in my office, next to our clogs and plastic bins, where they lived just beside my right knee as I wrote discharge summaries and prescribed prenatal vitamins.

The stash was a reminder that we may need to do it all again—and that when we did, we would once again be short on resources. Over the summer, and fall, when our COVID levels were low, we saw no evidence that they would stay that way: There were the long-standing testing shortages, the half-hearted quarantine measures, botched national public health messaging and responses. We took much needed vacation days. But with no meaningful strategic approach by the federal government to handle the virus, it was clear to all of us that it was just a matter of time before we were, once again, left to scramble.

In November, we saw cases around the city start to rise, and in December, those lines on all the graphs marched steadily, stratospherically upward. And here we are again, our hospital filling up with gasping patients. I admitted three patients with COVID pneumonia in pregnancy over Christmas, and a few more on New Year’s Day. Two of the baby monitors are now unpacked, ready to watch numbers beep and blink. We are doing this again.